Khotiv hillfort

Ukrainian: Хотівське городище | |

Southern view of Khotiv and Khotiv hillfort | |

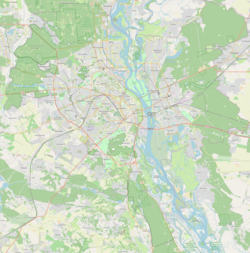

Location of the hillfort on a map of Kyiv | |

| Location | Khotiv, Obukhiv Raion, Kyiv Oblast, Ukraine |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 50°20′01″N 30°29′16″E / 50.33361°N 30.48778°E |

| Type | hillfort |

| Length | 1,000 m (3,300 ft) |

| Width | 700 m (2,300 ft) |

| Area | 31 ha (77 acres) inside the main rampart |

| History | |

| Founded | 7-6 century BC |

| Abandoned | 6-5 century BC or later |

| Periods | early Iron Age |

| Cultures | Scythian |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1948, 1965-1967, 2004, 2016 |

| Condition | partially ruined |

| Ownership | partially private |

| Public access | Yes |

Khotiv hillfort is a hillfort of early Iron Age (Scythian times, 6 century BC) in the village of Khotiv, Ukraine.

The hillfort adjoins the southern part of Kyiv, namely Feofaniya Park. It occupies a rhombic plateau 1000x700 m wide, bordered by valleys of the streams. All the plateau area, 31 ha, was surrounded with earth rampart, while the slope of the hill was fortified by a scarp with a berm and a moat beneath.[1] The rampart, scarp and berm are well preserved on the western and eastern edges, and remains of the moat are much less conspicuous now. It is supposed that the hillfort had 3 entrances: in the northern, eastern and southern part of the rampart.[2]

Khotiv hillfort has the status of an archaeological monument since 1965.[3] In 2007, official borders of the monument were cut down, and in 2009, the excluded areas became the place of house building. The northern part of the hillfort was demolished by building of a palace of Ukrainian billionaire Yuri Kosiuk.[4][5] Later, the works began in the southern and eastern parts of the hillfort, which are planned for building too.[6]

Exploration

[edit]The first scientific mention of the hillfort was made in 1848 by Ivan Fundukley, governor of Kyiv and notable historian. He mentions a local legend about some town which existed there.[7] In 1864, the hillfort was briefly described by another student of local history, Lavrentiy Pohilevich. He reports this legend in more details: in ancient times there was a town with a castle of a prince named Siriak.[8] The locality around the hillfort is still named Siriakove, and the first recording of this name dates from 1465.[9]

In 1873, Volodymyr Antonovych made more detailed description and drawing of the hillfort. He interpreted it as Zvenigorod, the fortress of Kievan Rus' known from chronicles.[10] But archaeological data of 20th century refuted this idea.

In 1917, a bronze Corinthian coin of 5 century BC was found on the hillfort during a botanical excursion. In 1918, fragments of Scythian pottery and some Slavic things dated from 8-10 centuries AD were found there.[9]

The first archaeological exploration of the hillfort was conducted in 1948 by the team from Institute of Archaeology in Kyiv headed by Ye. F. Pokrovska. They excavated 156 m2 in the northern projection of the hillfort.[2] Next expedition, headed by Ye. O. Pokrovska from the same Institute, worked in 1965-1967 and unearthed 508 m2 in the vicinity.[11][1]

In 2004, northern and western parts of the hillfort (6.75 ha) were explored with micromagnetic measurements. It revealed location of several ancient buildings, some of which were unearthed.[12] Some additional measurements were made in 2009.[5]

In 2016, new excavations were made on the western side of the hillfort, on the rampart.[13]

-

Khotiv hillfort (captioned as "Гора Городище" - "Mount Hillfort") on the map by General Staff of the Russian army, 1842.

-

Sketch of the Khotiv hillfort made by Volodymyr Antonovych in 1870s.

Finds

[edit]Like other hillforts of Scythian times, Khotiv hillfort had buildings only near the inner side of the rampart. The central area was empty and could be used for farming or for keeping of cattle, maybe during wars.[14] Discovered structures include dugouts and surface buildings with walls made of wood covered by clay. Fallen walls of several such buildings were excavated, some of them exceed 20 m in length.[5] Some buildings had stoves. Another notable object is an oval 1x1.5 m wide, paved with stones bearing marking of fire.[15]

The pottery from the hillfort include local and Greek one. The latter was identified as originating from Chios, Lesbos, Klazomenai and Samos.[16] Other ceramic finds from the hillfort include spindle whorls of various forms, a sinker, and small balls and "loafs" which can be votive offerings.[17]

A broken stone dish and a fragment of a stone axe or hammer, sling stones, sharpening stone with a hole, bone handle of an unknown tool, beads made of lead and yellow glass, as well as other things were also unearthed.

Bronze finds include a snake-like ring, pins, including nail-like ones, and arrowheads of various forms. Iron objects include knives, awls, pin and some arrowheads.[1][12]

Another notable find is a bone plate with a carving of a panther or a leopard in the Scythian animal style. Size of the plate is 4.7x1.8 cm. It could be a part of a bigger thing, e.g. a spoon or a mirror handle. Associated ceramics and arrowheads indicate that it belongs to the end of 6th century BC. Such carvings are rare on Scythian bone things, although more common on metallic ones.[14]

Plenty of animal bones imply that dwellers of the hillfort bred domestic animals, predominantly horses. Pigs, cows, sheep, goats and dogs were also held.[14] Dominance of horses differs Khotiv hillfort from other hillforts of forest steppe, which were dominated by cattle or pigs.[2] Its inhabitants hunted wild boars, deers, elks, bears and beavers, sometimes aurochs and hares. Sporadic bones of turtles, foxes, geese, ducks, crows and men were found.[14][2]

Finds from the hillfort date from Scythian times, approximately 6, or, according to other researchers, 6 to 5 century BC.[5][14] It was probably founded by people called Scythians-tillers by Herodotus. They were not Scythians in the strict sense, but they stayed under Scythian dominion and partially adopted their culture.[18]

Founders of the hillfort were nonmigratory. They practised agriculture and animal breeding, especially horse breeding. Hunting played a big role. Trade with Ancient Greek colonies was less intensive than on other hillforts of forest steppe. It is explained by larger distance.[2][11]

- Finds from the Khotiv hillfort

-

Pottery

-

Pottery

-

Bronze and iron arrowheads, lead bead, sharpening stone, ceramic spindle whorl etc.

-

Beast on a bone plate

-

Bronze nail-like pins

History after Scythians

[edit]Written sources allow to trace history of the hillfort since 1465, when the last Grand Prince of Kiev Semen Olelkovich granted it to prince Yuri Borisovich. After him, the hillfort consecutively belonged to several other people.[9][19] In 1588, prince Matviy Voronetsky transferred it to the possession of Kyiv Pechersk Lavra, where it remained for almost 200 years. In 1786, during secularization reform of Catherine the Great, the hillfort passed to the use of Khotiv inhabitants. From this time, it was covered by fields and gardens.[9]

Agricultural works, which lasted on the hillfort over 200 years, did not ruin the fortifications, but damaged the archaeological horizon.[20] In 1939, southwestern edge of the hillfort was damaged by a big landslide,[2] and in the late 1960s, by building of a dam on the nearby Vita stream.[21] The southern edge of the hillfort, already damaged by erosion, became fringed by more and more village houses.

Protection and building

[edit]Khotiv hillfort has the status of an archaeological monument since 1965, given by resolution of the Council of Ministers of the Ukrainian SSR.[3] In 1979, Kyiv City Council pronounced it one of archaeological reserves of Kyiv.[22] In 2001, Government of Ukraine included the hillfort in the State registry of immovable monuments of Ukraine as an archaeological monument of national significance.[23] In 2009, this status was confirmed by a new governmental resolution.[24]

Boundaries of the Archaeological reserve "Khotiv hillfort in the borders of fortification of Scythian times" were specified by Kyiv City Council in 1979 and confirmed by Kyiv City State Administration in 2002. These boundaries embraced the plateau with the fortification and adjacent slopes with total area of 48 ha.[25]

In 2007, Institute of monument protection research of the Ministry of Culture of Ukraine made documentation for the archaeological monument where its area was restricted to 16.49 ha in central and western parts of the plateau. All the fortifications were excluded from the monument area.[26] Approximately the same borders are stated in the development plan of Khotiv.[6]

In 2008, Khotiv village council transferred part of the land excluded from the monument to the possession of 5 building cooperatives for free. They received northeastern part of the hillfort (including all the eastern rampart with the scarp) and adjacent slope with total area 13 ha. After several years of splitting and resale, the land passed into the ownership of businessmen Victor Polishchuk, Liliya Rizva and Yuri Kosiuk. Parts of the hillfort which are in the possession of the former two owners are still intact, while Kosiuk's land became the site of an active building works.[4][27]

The building on the hillfort began in 2009. Initially its customer was unknown, and an information board on the building site announced construction of a new entrance to Feofaniya Park.[28] Gradually, a luxurious palace surrounded by terraces appeared there.[4][29] As of 2016, the northern part of the hillfort (one of the richest in remains of ancient buildings and enclosed with the highest rampart),[1] including its fortification, and the landscape of adjacent areas was demolished.[5] According to Yuri Kosiuk, "the building which is built is built in a chasm, and it has nothing to do with the hillfort".[4]

Changes occurred in the other parts of the hillfort as well. As of 2015, all the eastern part of the plateau was marked as a land intended for building in the Public cadastre map of Ukraine.[30][31] Many new privatized and leased land parcels appeared in the western and southeastern parts.[27][32]

In 2010–2012, a road stretched over all the southern part of the plateau. In the development plan of Khotiv, southern side of this road (named Parkova Street) is also intended for building.[6] Several big erosion zones in the southern part and a small ravine in the eastern end of the hillfort were buried with soil. This ravine, according to Ye. F. Pokrovska, head of the first archaeological exploration of the hillfort, could be an ancient entrance.[2]

In 2013, Institute of monument protection research of the Ministry of Culture of Ukraine made new documentation of Khotiv hillfort, approved by the Ministry same year. This document describes an archaeological reserve (with the same area as the archaeological monument on the 2007 scheme), an archaeological monument (approximately twice bigger, including all the plateau) and its protection zone (100–500 m wide). The palace was marked as a "dissonant building".[33]

In 2016, Institute of Archaeology of Ukrainian Academy of Sciences prepared one more documentation of the hillfort, where protected area includes almost 20 ha. It comprises the 16.5 ha from 2007 scheme plus the western border of the plateau with the rampart and scarp. Additionally, part of a buried erosion zone is included. In the same year, new borders were approved by Khotiv village council[34][35] and marked by red concrete pillars. Three stones with commemorative plaques and an information board were installed on the hillfort as well. Area of the archaeological monument stated on the board is 18.3 ha, and area of its protection zone (a strip along its western edge) is 1.04 ha. It excludes all the northern, southern and eastern parts of the hillfort (the latter still having a well-preserved rampart and scarp). The rest of the hillfort is planned for museumification.[36]

-

Northeastern edge of the hillfort in 2009 (demolished next year). The rampart and traces of the moat are seen in the background and in the right.

-

Western edge of the hillfort (2016). The scarp and trace of the rampart are seen.

-

The western scarp and adjoining hill, where an ancient entrance was situated according to some works[13] (2016).

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Петровська Є. О. Ранньоскіфські пам'ятки на південній околиці Києва / В кн.: Археологія. — К.: Наукова думка, 1970. — Т. XXIV. — С. 129—145.

- ^ a b c d e f g Покровська Є. Ф. Хотівське городище // Археологічні пам'ятки УРСР. — 1952. — Т. 4. — С. 12-20.

- ^ a b Постанова Ради Міністрів Української РСР від 21 липня 1965 р. № 711 "Про затвердження списку пам'ятників мистецтва, історії та археології Української РСР"

- ^ a b c d Будинок на кістках. "Слідство.Інфо". 26.06.2015.

- ^ a b c d e Дараган М., Орлюк М., Роменець А., Бондар К. Інтерпретація даних високоточної магнітної зйомки в складі археологічної ГІС (на прикладі Хотівського городища скіфської доби). 15th EAGE International Conference on Geoinformatics - Theoretical and Applied Aspects. 10–13 May 2016, Kyiv, Ukraine.

- ^ a b c Development plan of Khotiv village of Kyiv-Sviatoshyn Raion of Kyiv Oblast (Генеральний план с. Хотів Києво-Святошинського району Київської області) Archived 2017-04-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Фундуклей И. И. Обозрение могил, валов и городищ Киевской губернии. — К., 1848. — С. 36.

- ^ Похилевич Л.И. Сказание о населенных местностях Киевской губернии. — Киев: Киево-Печерская лавра. — 1864. Archived 2017-04-26 at the Wayback Machine — С. 30-31.

- ^ a b c d Добровольський Л. П. З минулого Хотівської околиці м. Києва // Записки історично-філологічного відділу ВУАН. Гол. ред. А. Кримський. Кн. XII. — К. : Українська Академія Наук, 1927. — 364 с. — С. 204—222.

- ^ Антонович В. Б. О местоположении древнего Киевского Звенигорода // Древности: Труды Московского археологического общества. — М.: Синодальная тип., 1876. — Т. VI, в. 1. — С. 41—46.

- ^ a b Петровская Е. А. Раскопки на Хотовском скифском городище в 1965-66 гг. / В кн.: Археологические исследования на Украине в 1965—1966 гг. — К.: Наукова думка, 1967. — Вып. І. — С. 106—109.

- ^ a b Ивакин Г. Ю., Дараган М. Н., Орлюк М. И., Кравченко Э. А., Куприй С. А. Геофизические и археологические исследования Хотовского городища скифской эпохи // Археологічні дослідження в Україні 2003—2004 рр.: Збірка наукових праць / За ред. Н. О. Гаврилюк. — Вип. 7. — Київ: ІА НАН України; Запоріжжя: Дике Поле, 2005. ISBN 966-8132-52-1 — С. 400—405.

- ^ a b Кравченко Е., Манігда О., Шелехань О. Хотівське городище: влаштування і інфраструктура (доповідь на Міжнародній археологічній конференції «Освоєння простору: житло, поселення, регіон», 27-28 жовтня 2016 р., Львів-Винники).

- ^ a b c d e Максимов Е. В., Петровская Е. А. Древности скифского времени Киевского Поднепровья / Под ред. Р. В. Терпиловского. — Полтава, 2008. С. 11-12, 39, 46, 53-54, 75. — 126 с.

- ^ Дараган М. Н., Орлюк М. И., Кравченко Э. А. Результаты геофизических исследований на Хотовском городище скифской эпохи // Археология и геоинформатика. Вып. 4. Москва: Институт археологии РАН, 2007.

- ^ Дараган М. Н. Античная керамика из Хотовского городища скифской эпохи // Боспорский феномен. Проблема соотношения письменных и археологических источников. — СПб., 2005 — С. 256—261.

- ^ Гречко Д. С. Мелкая глиняная пластика населения северодонецкой лесостепи скифского времени // Каменная скульптура и мелкая пластика древних и средневековых народов Евразии: сборник научных трудов / отв. ред. А. А. Тишкин. — Барнаул: Изд-во Аз Бука, 2007. — 156 с.: ил. — (Труды САИПИ. Вып. 3) — С. 18-20.

- ^ Телегин Д. Я. Там, где вырос Киев. — К., Наукова Думка, 1982. — С. 71-78.

- ^ Грушевський М. С. Кілька київських документів XV—XVI в. // Записки Наукового товариства імені Шевченка. Під ред. М. С. Грушевського. Том XI. — Львів, 1896 — С. 5, 14-18.

- ^ Statement about the condition of archaeological monument of national significance "Khotiv hillfort in the borders of the fortifications of Scythian times" (based on the order of Kyiv City State Administration from 17.05.2002 р. № 979). Ukrainian: Акт про стан археологічної пам'ятки національного значення Археологічного заповідника Хотівське городище в межах укріплень скіфського часу (на основі розпорядження Київської міської державної адміністрації від 17.05.2002 р. № 979). (Image). 19.04.2007.

- ^ Хотів: з давніх давен і до сьогодення (Khotiv - from ancient times and to this day) / За ред. В.К. Хільчевського (Edited - Valentyn Khilchevskyi). Kиїв: ДІА. — 2009. — 108 с. — С. 14 — ISBN 978-966-8311-51-2

- ^ Г.Ю. Івакін, С.І. Климовський. Проблеми охорони археологічних пам'яток Києва. АРОІКС. – К.: КНЛУ, 1999. – Вип. 3.

- ^ Постанова Кабінету Міністрів України від 27 грудня 2001 р. № 1761 "Про занесення пам'яток історії, монументального мистецтва та археології національного значення до Державного реєстру нерухомих пам'яток України"

- ^ Постанова Кабінету Міністрів України від 3 вересня 2009 р. № 928 «Про занесення об'єктів культурної спадщини національного значення до Державного реєстру нерухомих пам'яток України»

- ^ Розпорядження КМДА від 17.05.2002 р. № 979 "Про внесення доповнень до рішень виконкому Київської міської ради народних депутатів від 16.07.1979 р. № 920 «Про уточнення меж історико-культурних заповідників і зон охорони пам'яток історії та культури в м. Київ». The map of the borders see in Євсюков Т., Опенько І. Моніторинг особливо цінних земель із застосуванням технологій ДЗЗ та ГІС // Вісник Львівського національного аграрного університету. Сер : Економіка АПК. — 2013. — № 20(2). — С. 231-242.

- ^ Plan-scheme of the borders of the archaeological monument of national significance, the hillfort of early Iron Age (Scythian culture) in Khotiv village of Obukhiv Raion of Kyiv Oblast (with the conducted scientific substantiation taken into account). Ukrainian: План-схема меж пам'ятки археології національного значення - городища раннього залізного віку (скіфської культури) у с. Хотів Києво-Святошинського району Київської області (з урахуванням проведеного наукового обгрунтування) (image), accompanying letter to the plan-scheme by the State service of the national cultural heritage (image). 29.11.2007.

- ^ a b "На курячих ніжках". "Слідство.Інфо". 15.03.2017.

- ^ Загадка Хотівського городища: хто руйнує пам’ятку й навіщо? УНІАН. 28 жовтня 2009.

- ^ Video of the northern part of Khotiv hillfort in 2017.

- ^ Архітектура постреволюційного періоду. Хто забудовує Феофанію? Тиждень.UA. 25.07.2015.

- ^ "Public cadastre map of Ukraine". Archived from the original on 2017-04-09. Retrieved 2017-03-31.

- ^ Френди екс-заступника Кличка приватизували землю на межі Хотівського городища. Наші Гроші. 5.05.2016.

- ^ Plan-scheme of the location of the borders of the archaeological monument of national significance "Khotiv hillfort" and the borders of its protection zone. Approved by the order of the Ministry of Culture of Ukraine №1094, 5.11.2013. Ukrainian: План-схема розташування меж території пам'ятки археології національного значення "Хотівське городище" та меж її охоронної зони. Затверджено наказом Міністерства культури України від 5.11.2013 р. № 1094 (image.)

- ^ About the project of the resolution "About the establishment of the actual borders of the archaeological monument of national significance - the hillfort of Early Iron Age in Khotiv village. Ukrainian: "Про проект рішення "Про встановлення фактичних меж памятки археології національного значення - городища раннього залізного віку в с. Хотів". (image.). Khotiv village council, 30.06.2016, video of the meeting of the council.

- ^ Хотівська сільська рада розглянула питання про межі "Хотівського городища". ПравдаТУТ. 01.07.2016

- ^ Археологічні дослідження на території Хотівського городища: підсумки 2016 року Archived 2017-04-01 at the Wayback Machine. Прес-служба НАН України. 9.03.2017.

![The western scarp and adjoining hill, where an ancient entrance was situated according to some works[13] (2016).](/upwiki/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/47/%D0%A5%D0%BE%D1%82%D1%96%D0%B2%D1%81%D1%8C%D0%BA%D0%B5_%D0%B3%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B4%D0%B8%D1%89%D0%B5_0106-5410.jpg/240px-%D0%A5%D0%BE%D1%82%D1%96%D0%B2%D1%81%D1%8C%D0%BA%D0%B5_%D0%B3%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B4%D0%B8%D1%89%D0%B5_0106-5410.jpg)