Maria Radna Monastery

| Maria Radna Monastery | |

|---|---|

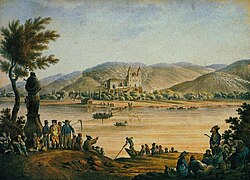

Frontal view of the church in June 2021 | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Roman Catholic |

| District | Roman Catholic Diocese of Timișoara |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Church |

| Patron | Saint Mary |

| Year consecrated | 1750 |

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | Radna, Romania |

| Geographic coordinates | 46°05′57″N 21°41′10″E / 46.09917°N 21.68611°E |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Baroque |

| Completed | 1722–1828 1911 |

| Height (max) | 67 m |

| Website | |

| https://www.basilicamariaradna.info/home | |

The Saint Mary Monastery church of Radna (Romanian: Mănăstirea Maria Radna, Hungarian: Máriaradnai kolostor) is an 18th century baroque-style church in Radna, Arad County, Romania, located within the Roman Catholic Diocese of Timișoara.[1] The monumental ensemble consists of the actual church and three other buildings, all historical and architectural monuments of the 18th and 19th centuries.[2]

History

[edit]

The first documentary mentions of monastic activity in this place date from around 1327. These mentions are related to the king of Hungary, Charles Robert of Anjou, who erected here a monastery and a church dedicated to Saint Louis of Toulouse, his uncle, both of which were entrusted to a group of Franciscan monks who came from Bosnia.

In the year 1520, a small chapel was built by a pious widow on the nearby hill, where the Franciscan monks refugees served on these banks of the Mureș River, when the Banat area was under Ottoman occupation. After the Banat region was conquered by the Ottomans in 1551, the chapel served the faithful and the Franciscan monks, refugees from the raiders on the northern shore of the Mureş river.[3]

In 1626 the Franciscan monastery was re-established at Radna. In 1642, P. Andrija Stipančić, a priest in Radna, after a long and arduous journey on foot to Constantinople and back, succeeds in obtaining, in exchange for a substantial tip, an "Embre" (firman) from the Sultan Ibrahim I for the renovation of his chapel. In the year 1668, a certain Gheorghe Vriconosa from Bosnia donated an "icon of the Mother of God" to the chapel of the Franciscan monks in Radna. The icon was printed on paper in the workshop of a master typographer in Italy. In September 1695, the chapel was set on fire by the Ottoman soldiers, being devastated to the very ground. Despite the fire, the "icon of the Mother of God" did not suffer any damage, being considered a miracle-working artifact honored by believers to this day. Only in the year 1750, thanks to canon Johannes Szlezak, the monastic settlement Maria Radna was officially recognized as a church and place of pilgrimage. In the same year, the place of pilgrimage to Maria-Radna was also officially recognized.[3]

In 1723, a new, larger church was built. In 1727, the construction of today's monastery with the west wing began. Between 1743 and 1747, the number of monks increasing significantly, the south wing was added. In 1756, on 7 July, on the feast of Pentecost, the foundation stone of a new church for Maria Radna was laid, the old church already being too small.[3]

Between the years 1769–1771, the magnificent silver frame was made for the miraculous icon which is still visible as of today.

In the year 1992, the church was brought up to the rank of Minor Basilica with the patronage of 'Mother of Graces', by Pope John Paul II. In the year 2003, the Franciscan monks left the monastery, the parish and the place of pilgrimage being looked after by the diocesan clergy ever since.[4]

In 2013, as part of a project co-financed by the European Union, the Maria Radna complex, classified as a class-A historic monument, underwent a complete renovation, the aim being the revitalization of local tourism.[3]

The "icon of the Mother of God"

[edit]

According to a sum of reports dating from before 1750, it appears that the Miraculous Icon, a representation of the Blessed Virgin Mary on Mount Carmel, had been resting in the nearby locality of Radna since 1668. An old Bosnian resident had bought it from an itinerant Italian merchant. Years later, the old man donated the icon to the church. It was printed after 1660 in northern Italy, more precisely in the Remondi printing house in Bassano del Grappa (province of Vicenza). Hundreds or even thousands of copies of the icon left the printing house at that time. The sacred image, measuring 477x705 mm, represents the Holy Virgin Mary with the Baby Jesus in her arms, and a scapular can also be seen in the Virgin's hands. On the edges of the image, there are group of imprimed small scenes with corresponding texts in Italian, which describe events with people in need who were miraculously helped by the Mother of God. Under the image with the Holy Virgin and the Baby Jesus, there is a small text written in Italian which says: "La Beatissima Vergine del Carmine", and which means "Holy Virgin of Carmel". Beneath this text, there is a representation of people on fire, which signify the souls of deceased people who have arrived in the Purgatory.[5]

The monastery's museum

[edit]The Maria Radna Museum has a rich history which dates back to the year 1325. This museum displays a large number of artifacts of the Franciscan order, as well as a collection of more than 2,500 paintings donated by various people to the church, who claimed they symbolize the miracles they experienced during their lives. The current collection of paintings is actually the second one in the building and was started in 1850, after the first collection was destroyed at that time by an abbot who was angered by the multitude of existing paintings. After their destruction, the next abbot decided to collect them again, currently reaching a number of over 2,500 copies.[6]

The Holy Cross' road

[edit]The "Way of the Cross", a local popular reinterpretation of the Stations of the Cross, climbs the hill from behind the monastery, guarded by statues of saints in stone niches. There are two such "Ways of the Cross". The first one, with 14 stops, represents the Path of Sorrow, which the Savior traversed until his Crucifixion. It was laid out in 1888 and rebuilt after the First World War. The second path, laid out in 1920, is a Path of Joy, the glorious path after the Resurrection.[7][8]

Gallery

[edit]-

Chapel of Our Lady of Lourdes

-

The church's naos

-

Main altar of the church

-

Paintings on the church's ceiling

-

Interior of the church

-

Frontal view of the church (2011)

-

North-west quarters of the monastery

-

Monastery's museum halls

-

Monastery's museum halls

Further reading

[edit]- Martin Roos: Maria Radna. Ein Wallfahrtsort im Südosten Europas, vol. I, Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg, 1998, ISBN 3-7954-1170-X

- Martin Roos: Maria Radna. Ein Wallfahrtsort im Südosten Europas, vol. II, Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg, 2004, ISBN 3-7954-1183-1

- Swantje Volkmann: Die Architektur des 18. Jahrhunderts im Temescher Banat, Heidelberg, 2001

External links

[edit]- Mănăstirea Maria Radna Archived 31 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine

References

[edit]- ^ "Ministerul Culturii – Lista Monumentelor Istorice" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ "Mănăstirea „Sfânta Maria"- Radna". aradcityguide.ro (in Romanian). Arad City Guide. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Basilica Maria Radna CNIPT Arad". cniptarad.ro (in Romanian). Centrul de Informare Turistică Arad. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ aradcityguide.ro. "Mănăstirea Sfânta Maria-Radna".

- ^ Both, Ștefan (6 June 2018). "Povestea icoanei făcătoare de minuni din basilica Maria-Radna, care vreme de 350 de ani ar fi vindecat mii de oameni". Adevărul (in Romanian). Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ Both, Ștefan (15 August 2015). "Povestea colecţiei de icoane şi tablouri de la Mănăstirea Maria Radna: credincioşii le-au lăsat ca semn de recunoştinţă pentru vindecările miraculoase". Adevărul (in Romanian). Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ^ Decean, Dana (4 October 2021). ""Radna cea frumoasă" a lui Ioan Slavici, mănăstirea unde se vine pe jos de la sute de kilometri". ghidulbanatului.ro (in Romanian). Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ "PELERINAJ LA MARIA RADNA IMAGINI RARE". infogiarmata.ro (in Romanian). Info Giarmata. 11 February 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.