Satellite geodesy

| Geodesy |

|---|

|

Satellite geodesy is geodesy by means of artificial satellites—the measurement of the form and dimensions of Earth, the location of objects on its surface and the figure of the Earth's gravity field by means of artificial satellite techniques. It belongs to the broader field of space geodesy. Traditional astronomical geodesy is not commonly considered a part of satellite geodesy, although there is considerable overlap between the techniques.[1]: 2

The main goals of satellite geodesy are:

- Determination of the figure of the Earth, positioning, and navigation (geometric satellite geodesy)[1]: 3

- Determination of geoid, Earth's gravity field and its temporal variations (dynamical satellite geodesy[2] or satellite physical geodesy)

- Measurement of geodynamical phenomena, such as crustal dynamics and polar motion[1]: 4 [1]: 1

Satellite geodetic data and methods can be applied to diverse fields such as navigation, hydrography, oceanography and geophysics. Satellite geodesy relies heavily on orbital mechanics.

History

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2011) |

First steps (1957–1970)

[edit]Satellite geodesy began shortly after the launch of Sputnik in 1957. Observations of Explorer 1 and Sputnik 2 in 1958 allowed for an accurate determination of Earth's flattening.[1]: 5 The 1960s saw the launch of the Doppler satellite Transit-1B and the balloon satellites Echo 1, Echo 2, and PAGEOS. The first dedicated geodetic satellite was ANNA-1B, a collaborative effort between NASA, the DoD, and other civilian agencies.[3]: 51 ANNA-1B carried the first of the US Army's SECOR (Sequential Collation of Range) instruments. These missions led to the accurate determination of the leading spherical harmonic coefficients of the geopotential, the general shape of the geoid, and linked the world's geodetic datums.[1]: 6

Soviet military satellites undertook geodesic missions to assist in ICBM targeting in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Toward the World Geodetic System (1970–1990)

[edit]

The Transit satellite system was used extensively for Doppler surveying, navigation, and positioning. Observations of satellites in the 1970s by worldwide triangulation networks allowed for the establishment of the World Geodetic System. The development of GPS by the United States in the 1980s allowed for precise navigation and positioning and soon became a standard tool in surveying. In the 1980s and 1990s satellite geodesy began to be used for monitoring of geodynamic phenomena, such as crustal motion, Earth rotation, and polar motion.

Modern era (1990–present)

[edit]

The 1990s were focused on the development of permanent geodetic networks and reference frames.[1]: 7 Dedicated satellites were launched to measure Earth's gravity field in the 2000s, such as CHAMP, GRACE, and GOCE.[1]: 2

Measurement techniques

[edit]

Techniques of satellite geodesy may be classified by instrument platform: A satellite may

- be observed with ground-based instruments (Earth-to-space-methods),

- carry an instrument or sensor as part of its payload to observe the Earth (space-to-Earth methods),

- or use its instruments to track or be tracked by another satellite (space-to-space methods).[1]: 6

Earth-to-space methods (satellite tracking)

[edit]Radio techniques

[edit]Global navigation satellite systems are dedicated radio positioning services, which can locate a receiver to within a few meters. The most prominent system, GPS, consists of a constellation of 31 satellites (as of December 2013) in high, 12-hour circular orbits, distributed in six planes with 55° inclinations. The principle of location is based on trilateration. Each satellite transmits a precise ephemeris with information on its own position and a message containing the exact time of transmission. The receiver compares this time of transmission with its own clock at the time of reception and multiplies the difference by the speed of light to obtain a "pseudorange." Four pseudoranges are needed to obtain the precise time and the receiver's position within a few meters. More sophisticated methods, such as real-time kinematic (RTK) can yield positions to within a few millimeters.

In geodesy, GNSS is used as an economical tool for surveying and time transfer.[4] It is also used for monitoring Earth's rotation, polar motion, and crustal dynamics.[4] The presence of the GPS signal in space also makes it suitable for orbit determination and satellite-to-satellite tracking.

Examples: GPS, GLONASS, Galileo

Doppler techniques

[edit]Doppler positioning involves recording the Doppler shift of a radio signal of stable frequency emitted from a satellite as the satellite approaches and recedes from the observer. The observed frequency depends on the radial velocity of the satellite relative to the observer, which is constrained by orbital mechanics. If the observer knows the orbit of the satellite, then recording the Doppler profile determines the observer's position. Conversely, if the observer's position is precisely known, then the orbit of the satellite can be determined and used to study the Earth's gravity. In DORIS, the ground station emits the signal and the satellite receives.

Examples: Transit, DORIS, Argos

Optical triangulation

[edit]In optical triangulation, the satellite can be used as a very high target for triangulation and can be used to ascertain the geometric relationship between multiple observing stations. Optical triangulation with the BC-4, PC-1000, MOTS, or Baker Nunn cameras consisted of photographic observations of a satellite, or flashing light on the satellite, against a background of stars. The stars, whose positions were accurately determined, provided a framework on the photographic plate or film for a determination of precise directions from camera station to satellite. Geodetic positioning work with cameras was usually performed with one camera observing simultaneously with one or more other cameras. Camera systems are weather dependent and that is one major reason why they fell out of use by the 1980s.[3]: 51

Examples: PAGEOS, Project Echo, ANNA 1B

Laser ranging

[edit]In satellite laser ranging (SLR) a global network of observation stations measure the round trip time of flight of ultrashort pulses of light to satellites equipped with retroreflectors. This provides instantaneous range measurements of millimeter level precision which can be accumulated to provide accurate orbit parameters, gravity field parameters (from the orbit perturbations), Earth rotation parameters, tidal Earth's deformations, coordinates and velocities of SLR stations, and other substantial geodetic data. Satellite laser ranging is a proven geodetic technique with significant potential for important contributions to scientific studies of the Earth/Atmosphere/Oceans system. It is the most accurate technique currently available to determine the geocentric position of an Earth satellite, allowing for the precise calibration of radar altimeters and separation of long-term instrumentation drift from secular changes in ocean surface topography. Satellite laser ranging contributes to the definition of the international terrestrial reference frames by providing the information about the scale and the origin of the reference frame, the so-called geocenter coordinates.[5]

Example: LAGEOS

Space-to-Earth methods

[edit]Altimetry

[edit]

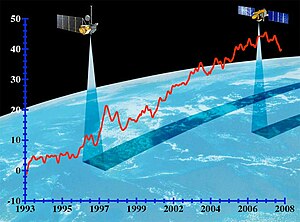

Satellites such as Seasat (1978) and TOPEX/Poseidon (1992-2006) used advanced dual-band radar altimeters to measure the height of the Earth's surface (sea, ice, and terrestrial surfaces) from a spacecraft. Jason-1 began in 2001, Jason-2 in 2008 and Jason-3 in January 2016. That measurement, coupled with orbital elements (possibly augmented by GPS), enables determination of the terrain. The two different wavelengths of radio waves used permit the altimeter to automatically correct for varying delays in the ionosphere.

Spaceborne radar altimeters have proven to be superb tools for mapping ocean-surface topography, the hills and valleys of the sea surface. These instruments send a microwave pulse to the ocean's surface and record the time it takes to return. A microwave radiometer corrects any delay that may be caused by water vapor in the atmosphere. Other corrections are also required to account for the influence of electrons in the ionosphere and the dry air mass of the atmosphere. Combining these data with the precise location of the spacecraft makes it possible to determine sea-surface height to within a few centimeters (about one inch). The strength and shape of the returning signal also provides information on wind speed and the height of ocean waves. These data are used in ocean models to calculate the speed and direction of ocean currents and the amount and location of heat stored in the ocean, which in turn reveals global climate variations.

Laser altimetry

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2011) |

A laser altimeter uses the round-trip flight-time of a beam of light at optical or infrared wavelengths to determine the spacecraft's altitude or, conversely, the ground topography.

Radar altimetry

[edit]A radar altimeter uses the round-trip flight-time of a microwave pulse between the satellite and the Earth's surface to determine the distance between the spacecraft and the surface. From this distance or height, the local surface effects such as tides, winds and currents are removed to obtain the satellite height above the geoid. With a precise ephemeris available for the satellite, the geocentric position and ellipsoidal height of the satellite are available for any given observation time. It is then possible to compute the geoid height by subtracting the measured altitude from the ellipsoidal height. This allows direct measurement of the geoid, since the ocean surface closely follows the geoid.[3]: 64 The difference between the ocean surface and the actual geoid gives ocean surface topography.

Examples: Seasat, Geosat, TOPEX/Poseidon, ERS-1, ERS-2, Jason-1, Jason-2, Envisat, SWOT (satellite)

Interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR)

[edit]Interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR) is a radar technique used in geodesy and remote sensing. This geodetic method uses two or more synthetic aperture radar (SAR) images to generate maps of surface deformation or digital elevation, using differences in the phase of the waves returning to the satellite.[6][7][8] The technique can potentially measure centimetre-scale changes in deformation over timespans of days to years. It has applications for geophysical monitoring of natural hazards, for example earthquakes, volcanoes and landslides, and also in structural engineering, in particular monitoring of subsidence and structural stability.

Example: Seasat, TerraSAR-X

Space-to-space methods

[edit]Gravity gradiometry

[edit]A gravity gradiometer can independently determine the components of the gravity vector on a real-time basis. A gravity gradient is simply the spatial derivative of the gravity vector. The gradient can be thought of as the rate of change of a component of the gravity vector as measured over a small distance. Hence, the gradient can be measured by determining the difference in gravity at two close but distinct points. This principle is embodied in several recent moving-base instruments. The gravity gradient at a point is a tensor, since it is the derivative of each component of the gravity vector taken in each sensitive axis. Thus, the value of any component of the gravity vector can be known all along the path of the vehicle if gravity gradiometers are included in the system and their outputs are integrated by the system computer. An accurate gravity model will be computed in real-time and a continuous map of normal gravity, elevation, and anomalous gravity will be available.[3]: 71

Example: GOCE

Satellite-to-satellite tracking

[edit]This technique uses satellites to track other satellites. There are a number of variations which may be used for specific purposes such as gravity field investigations and orbit improvement.

- A high altitude satellite may act as a relay from ground tracking stations to a low altitude satellite. In this way, low altitude satellites may be observed when they are not accessible to ground stations. In this type of tracking, a signal generated by a tracking station is received by the relay satellite and then retransmitted to a lower altitude satellite. This signal is then returned to the ground station by the same path.

- Two low altitude satellites can track one another observing mutual orbital variations caused by gravity field irregularities. A prime example of this is GRACE.

- Several high altitude satellites with accurately known orbits, such as GPS satellites, may be used to fix the position of a low altitude satellite.

These examples present a few of the possibilities for the application of satellite-to-satellite tracking. Satellite-to-satellite tracking data was first collected and analyzed in a high-low configuration between ATS-6 and GEOS-3. The data was studied to evaluate its potential for both orbit and gravitational model refinement.[3]: 68 Example: GRACE

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2011) |

List of geodetic satellites

[edit]- ANNA-1B

- Beidou

- BLITS

- CHAMP

- Diadème

- Echo

- Envisat

- ERS-1

- ERS-2

- Etalon

- Experimental Geodetic Payload "Ajisai"

- Explorer program

- Galileo

- Geo-IK-2

- GEOS-3

- Geosat

- Geosat Follow-On

- GFZ-1[9]

- GLONASS

- GRACE

- GOCE

- GPS

- ICESat-1

- ICESat-2

- LAGEOS

- LARES

- Larets

- H-IIA-LRE[10]

- PAGEOS

- Seasat

- Starlette and Stella

- TOPEX/Poseidon

- TRANSIT

- WESTPAC[11]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Seeber, Gunter (2003). Satellite geodesy. Berlin New York: Walter de Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110200089. ISBN 978-3-11-017549-3.

- ^ Sosnica, Krzysztof (2014). Determination of Precise Satellite Orbits and Geodetic Parameters using Satellite Laser Ranging. Bern: Astronomical Institute, University of Bern, Switzerland. p. 5. ISBN 978-8393889808.

- ^ a b c d e Defense Mapping Agency (1983). Geodesy for the Layman (PDF) (Report). United States Air Force.

- ^ a b Ogaja, Clement (2022). Introduction to GNSS Geodesy: Foundations of Precise Positioning Using Global Navigation Satellite Systems. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG. ISBN 978-3-030-91821-7.

- ^ Sosnica, Krzysztof (2014). Determination of Precise Satellite Orbits and Geodetic Parameters using Satellite Laser Ranging. Bern: Astronomical Institute, University of Bern, Switzerland. p. 6. ISBN 978-8393889808.

- ^ Massonnet, D.; Feigl, K. L. (1998), "Radar interferometry and its application to changes in the earth's surface", Rev. Geophys., vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 441–500, Bibcode:1998RvGeo..36..441M, doi:10.1029/97RG03139, S2CID 24519422

- ^ Burgmann, R.; Rosen, P.A.; Fielding, E.J. (2000), "Synthetic aperture radar interferometry to measure Earth's surface topography and its deformation", Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, vol. 28, pp. 169–209, Bibcode:2000AREPS..28..169B, doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.28.1.169

- ^ Hanssen, Ramon F. (2001), Radar Interferometry: Data Interpretation and Error Analysis, Kluwer Academic, ISBN 9780792369455

- ^ "International Laser Ranging Service". Ilrs.gsfc.nasa.gov. 2012-09-17. Retrieved 2022-08-20.

- ^ H2A-LRE

- ^ "International Laser Ranging Service". Ilrs.gsfc.nasa.gov. 2012-09-17. Retrieved 2022-08-20.

Attribution

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Defense Mapping Agency (1983). Geodesy for the Layman (PDF) (Report). United States Air Force. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-05-13. Retrieved 2021-02-19.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Defense Mapping Agency (1983). Geodesy for the Layman (PDF) (Report). United States Air Force. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-05-13. Retrieved 2021-02-19.

Further reading

[edit]- François Barlier; Michel Lefebvre (2001), A new look at planet Earth: Satellite geodesy and geosciences (PDF), Kluwer Academic Publishers

- Smith, David E. and Turcotte, Donald L. (eds.) (1993). Contributions of Space Geodesy to Geodynamics: Crustal Dynamics Vol. 23, Earth Dynamics Vol. 24, Technology Vol. 25, American Geophysical Union Geodynamics Series ISSN 0277-6669.