Tomb and Khanqah of Khawand Tughay

| Tomb and Khanqah of Khawand Tughay | |

|---|---|

Iwan and north dome chamber | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| Patron | Khawand Toghay |

| Location | |

| Location | Cairo, Egypt |

| Geographic coordinates | 30°02'33.1"N 31°16'15.4"E |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Islamic architecture, Mamluk architecture |

| Completed | 1348 |

The Tomb and Khanqa of Khawand Tughay (الخوند طوغاى) was built in Cairo, Egypt in 1348[1] by Khawand Tughay, also known as Umm Anuk (أم أنوك). It is located at the Northern Cemetery, in the City of the Dead, to the north of the Citadel of Saladin. It is a distinguished Mamluk monument not only for its architectural qualities, but also for having a woman as a patron.

History

[edit]There is no record about Khawand Tughay's date and place of birth. What is known is that she was an enslaved woman purchased in Damascus and sent to al-Nasir Mohammad Ibn Qalawun, the ninth Bahri Mamluk sultan, in 720 AH / 1320 CE. They had a romantic relationship and after the birth of their son Anuk in 721 AH / 1321 CE, she married him and received the title[2] al-khawand[3] al-kubra (senior princess / grand lady).

In addition to her sumptuous mausoleum and khanqah, historical accounts give us the dimension of her importance for the court and for Cairo's social life. Royal women had the pilgrimage to Mecca as a recorded symbol of their piety and power, and the earliest account[4] of this journey by a royal woman is that of Khawand Tughay. Her first pilgrimage was in 721 AH / 1322 CE, and it was the first time[5] a Mamluk sultan's wife went on this trip. As expected, it was very luxurious. Her caravan included members of the court, a ceremonial orchestra, camels carrying vegetables and cows to provide her with fresh milk and toasted cheese[6] along the journey. Such was the importance of this event that, at her request,[7] al-Nasir suspended the taxes on wheat in Mecca and hosted a feast on the return of the caravan after the three-month journey.[2] It is reported[2] that “she saw more happiness than any other of the wives of Turkish [that is, Mamluk] kings in Egypt” and that she was the most prestigious of 13 wives[8] of al-Nasir Muhammad.

Having an honorable and esteemed position at the court, she could afford her interest in architecture - she bought a house,[5] a hammam and built her mausoleum and khanqah. After the sultan's death, she continued to live at the citadel and was appointed guardian of his son al-Nasir Hasan.

Tughay died in 749 AH / December 1348 - January 1349 CE, during the plague. She left instructions to free all of her enslaved girls.[5]

Architecture

[edit]Originally built[9] as a khanqah with a vaulted iwan and two domed mausoleums, the surviving parts of the building consist of a pishtaq iwan flanked by the tomb of Tughay on one side and a chamber on the other, which was originally domed. Some remains indicate that one of the façades of the khanqah had a row of vaulted cells - these were living units[7] for the Sufis. The minaret, located at the main entrance, was destroyed. There was a waterwheel on the site.

The vaulted iwan is in a style of earlier Persian architecture (common in Mamluk buildings) and it has a Qur’anic inscription band running along its three walls, as in the main iwan of the Sultan Hasan complex. These two features suggest that the buildings of Tughay and Hasan might have been designed by the same architect.[10] Just below the vault there are 6 hexagonal openings.

The walls on either side of the qibla wall have a pointed arch that connects this area with the chambers. Each of these doors had a semi-circular decorative brick arch above the lintel. As it stands today, in the north wall of the iwan there is a rectangular opening in the center of the arch and in the south wall the arch is completely open to the chamber.

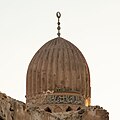

The dome

[edit]The dome, in a cylindrical shape curving at the top,[11] is made of brick masonry. Its exterior shape has 32 ribs and 24 niches[1] in the drum. The ribs are the earliest variation on the simple, plain dome, and may be seen in the Fatimid mausoleums in Cairo, as in the Mashhad of Sayyida Ruqayya (528 AH / 1133 CE). The earliest example of a Mamluk dome with 32 ribs is the Tomb of al-Sawabi (684 AH / 1285 CE).

The zone of transition of the chamber with the missing dome is made of one muqarna in each squinch, in a simpler design than that of the tomb. It is possible that it is a reconstruction of the original building, as there are records of the minaret's destruction during the invasion of Cairo by Napoleon.

The decoration

[edit]

In the iwan, three stucco medallions decorate the walls. The central one is above the mihrab (instead of the oculus that was so common in Cairo mosques) and the other two are centered in the width of the right and left walls. They have inscriptions, arabesques and 6 bosses with a floral pattern (the text is currently only readable on the south and north medallions). Their design resembles contemporary metal work and there are only three[5] other contemporary examples of such features in medallions in Mamluk architecture in Cairo. The bosses with floral patterns and the high relief borders also highlight the uniqueness of this building. There are two blind windows to either side of the central medallion and both have foliated decoration in their grills.

The mihrab consists of two pointed arches and its conche and spandrels are made of stucco with some remaining decoration. A feature worth noting is the bosses that were originally on the spandrels, in Ilkhanid style, similar[12] to those of the extant Qasr al-Ablaq (712 AH / 1313-14 CE), suggesting they were made by a Tabrizi workshop in Cairo. There is a band along the spandrels with arabesque motifs. The decorations would have been painted. There is a rectangular niche to either side of the mihrab.

Carved crenelations run all along the building, as it is usual in Cairo's Islamic buildings.

The courtyard entrance to Tughay's tomb has a rectangular frame with a muqarnas vault. On either side of the door, black and white ablaq jambs with an inscription on the second black stone (from top to bottom). Just above the door, a blank rectangular space where there probably was an inscription, as this was common in Islamic buildings. On top of this, there is a mushahar joggled voussoir and a small window above it.

On the interior of Tughay's dome there are plain 3-layered muqarnas squinches, similar to those in the Tomb of al-Salih Najm al-Din Ayyub (637-647 AH / 1240-50 CE). Above the 24 niches, in the base of the dome, there is a band of inscription and in the center of the dome there is an epigraphic medallion.

The inscriptions

[edit]There are eight surviving inscriptions in the building,[13] all Qur’anic and in naskh script. Five are made in carved stucco, two in stone (one carved and one inlaid) and one in tile mosaic.

The inscription bands in the exterior and interior base of the dome have the same text - Sura 2, Aya 255 (the Throne Verse).[13] The one on the interior has a foliated border with a foliated background and one lotus flower, the latter a feature that shows the growing Chinese influence on Cairene art and architectural decoration.[11] The inscription on the exterior of the dome is in tile mosaic with a blue background and white letters. It is a bit unusual, since it is one of only 13 documented Mamluk monuments with a tile mosaic.[5] This band also has cartouches with knots and a 6-pointed star in the center.

The epigraphic medallion in the apex of the dome has arabesque borders and, in the center, a 12-pointed star with medallions.[13]

The inscription band in the north, west and south façades have the Sura 36, Aya 1-19.[13]

The jambs of the portal to the north chamber have the Sura 44, Aya 51 to 53 ending at استبرق.[13]

Around the arch of the iwan, the inscription is Sura 48, Aya 1-2.[13]

Inside the iwan, in the qibla wall, the inscription is Sura 36, Aya 1-7.[13]

The medallions have the Sura 2, Aya 256-257 ending at النور. The text starts on the south medallion and finishes on the north one.[13]

Photos of the inscriptions

[edit]Photo gallery

[edit]-

Entrance portal to north chamber

-

Entrance portal to north chamber

-

Muqarnas vault in the entrance portal to north chamber

-

The dome

-

Iwan, epigraphic medallions and entrance to south chamber

-

Mihrab in the north chamber

-

Mihrab in the north chamber

-

North chamber

-

South chamber

-

Iwan, epigraphic medallion and view to the north chamber

-

Mihrab in the iwan

-

South chamber

-

View from south chamber to north chamber

-

Dome

-

South façade

-

South façade, view from the street

-

View from the street

-

View from the street

-

View from next door cemetery

-

View from next door cemetery

-

View from next door cemetery

-

View from a close by cemetery

References

[edit]- ^ a b O'Kane, Bernard (2021). "The Design of Cairo's Masonry Domes". Studies in Arab Architecture. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9781474474887.

- ^ a b c Williams, Caroline (1994). "The Mosque of Sitt Hadaq". Muqarnas. 11.

- ^ Mohamed Montser Moustafa, Youssra; Abd El Rahman Mahmoud, Samah; Abd El-Razik, Shaaban Samir (2023). "Women and their Architectural Contributions in the Bahri Mamluk State". Minia Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research. 16. NOTE: Khawand: A title that was common in the Mamluk era. It conveys the meaning of respect and is used to address males and females alike. It means master / lady / princess.

- ^ Behrens-Abouseif, Doris (1997). "The Mahmal Legend and the Pilgrimage of the Ladies of the Mamluk Court". Mamluk Studies Review. 1.

- ^ a b c d e Karam, Amina (2019). Women, Architecture and Representation in Mamluk Cairo (MA Thesis - American University in Cairo). Cairo.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Brack, Yoni. "A Mongol Princess Making hajj: The Biography of El Qutlugh Daughter of AbaghaIlkhan (r. 1265-82)". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 21 (3).

- ^ a b al-Harithy, Howayda (2005). "Female Patronage of Mamluk Architecture in Cairo". Beyond the Exotic: Women's Histories in Islamic Studies. New York: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815630555.

- ^ "Person Sheet: al-Nasir Muhammad ibn Qalawun". Mamluk Studies Resources: The Middle East Documentation Center at The University of Chicago.

- ^ Williams, Caroline (2008). Islamic Monuments in Cairo: The Practical Guide. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-416-205-3.

- ^ Kahil, Abdallah (2006). "The Architect/s of the Sultan Ḥasan Complex in Cairo". Artibus Asiae. 66 (2).

- ^ a b Behrens-Abouseif, Doris (2008). Cairo of the Mamluks: A History of the Architecture and its Culture. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 9789774160776.

- ^ Isaac Bakhoum, Diana (2016). "The Foundation of a Tabrizi Workshop in Cairo". Muqarnas. 33.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "The Monumental Inscriptions of Historic Cairo".