Участник:Jaskirat.mj/Массовые убийства при коммунистических режимах

Эта страница участника предлагается для быстрого удаления. |

Быстрое удаление этой страницы оспаривается. |

Различные авторы писали о событиях коммунистических режимов 20-го века, которые привели к избыточной смертности, например, избыточной смертности в Советском Союзе при Иосифе Сталине. Некоторые авторы утверждают, что существует коммунистическое число погибших, оценки смертности которых сильно варьируются в зависимости от определений смертей, которые в них включены, от минимальных 10-20 миллионов до максимальных более 100 миллионов, которые были раскритикованы несколькими учеными как идеологически мотивированные и завышенные. Оценки смертности, сделанные несколькими исследователями геноцида, которые в основном заинтересованы в установлении закономерностей, а не в точности данных, для чего они должны полагаться на экспертов и специалистов по странам, при сгруппированных коммунистических режимах также сильно варьируются, опять же в зависимости от определений смертей, которые в них включены. Более высокие оценки учитывают убийства, совершенные коммунистическими режимами против гражданского населения, включая казни, голод, смерть во время насильственных депортаций и тюремного заключения, а также смерть в результате принудительного труда. Оценки подвергаются критике, особенно те, которые находятся в верхней части спектра, со стороны других исследователей геноцида и исследователей коммунизма за неточность из-за неполноты данных, методологии, раздутости за счет подсчета любых избыточных смертей, игнорирования жизней, спасенных коммунистической модернизацией, и самого процесса подсчета и группировки ("общий коммунизм"), а также нескольких выбранных событий (гражданская война или связанные с войной смерти и голод, которые не должны учитываться и составляют большую часть более высоких оценок, составляя большинство смертей при коммунистических режимах), которые не подходят под наиболее принятое определение и категорию массовых убийств (50 000 убийств в течение пяти лет), и должны быть отнесены к категории избыточных смертей или событий массовой смертности, а не к массовым убийствам при коммунистических режимах.

Среди исследователей геноцида, которые не достигли статуса мейнстрима в политологии, и исследователей коммунизма нет единого мнения о том, представляли ли некоторые, большинство или все события массовые убийства. Также нет единого мнения относительно общей терминологии, и события по-разному называют избыточной смертностью или массовыми смертями; другие термины, используемые для определения некоторых из таких убийств, включают классицид, преступления против человечности, демоцид, геноцид, политицид и репрессии. Ученые утверждают, что большинство коммунистических режимов не занимались массовыми убийствами, а некоторые, в частности Бенджамин Валентино, предлагают вместо этого категорию коммунистических массовых убийств, наряду с колониальными, контрпартизанскими и этническими массовыми убийствами, как подтип бесправных массовых убийств, пытаясь отличить их от массовых убийств по принуждению. Исследователи геноцида, такие как Адам Джонс и Валентино, могли лишь подтвердить, что массовые убийства в соответствии с наиболее широко принятым определением, вероятно, имели место при режимах Иосифа Сталина, Мао Цзэдуна и Пол Пота, при этом отметив, что "общие массовые убийства", т.е. убийства в соответствии с гораздо более низким определением. как популяризировал Стефан Куртуа в своем введении к "Черной книге коммунизма" и подверг критике со стороны других ученых; некоторые, такие как Валентино, пытаются объяснить, как и почему большинство коммунистических режимов смогли избежать эксцессов трех наиболее радикальных режимов (Сталина, Мао и Пол Пота). Связь между коммунистической идеологией и массовыми убийствами была предложена некоторыми исследователями геноцида в контексте тоталитаризма (Рудольф Руммель) и отвергнута другими (Валентино), а также исследователями коммунизма, которые отвергают общую группировку коммунизма.

Хотя ни одно коммунистическое правительство не было осуждено за геноцид, бывшие члены правительства были признаны виновными в убийствах, а бывшие коммунистические режимы пытались дать концептуальное определение коммунистическому геноциду. Камбоджа и Эфиопия судили и осудили бывших членов правительства за геноцид, попытка Эстонии судить Арнольда Мери за геноцид была остановлена его смертью, а в Чехии отрицание коммунистического геноцида стало уголовным преступлением, а польское правительство обратилось за помощью к России в определении массовых убийств поляков советскими коммунистами как геноцида. В бывших коммунистических режимах проводились исследования памяти о том, как запоминаются эти события. Нарратив жертв коммунизма, популяризированный и названный в честь Мемориального фонда жертв коммунизма, стал общепринятой наукой, как часть теории двойного геноцида, в Восточной Европе и среди антикоммунистов в целом, но отвергается большинством западноевропейских и других ученых. Она критикуется учеными как политически мотивированная, чрезмерное упрощение и пример тривиализации Холокоста за приравнивание событий к Холокосту, выдвигая версию о коммунистическом или красном Холокосте.

Попытки предложить общую терминологию

Для описания преднамеренного убийства большого количества некомбатантов используются различные общие термины.[1][a][b][c][d][e] По словам историка Антона Вайс-Вендта, область сравнительного изучения геноцида, которая редко появляется в основных дисциплинарных журналах, несмотря на рост исследований и интереса, благодаря своим гуманитарным корням и опоре на методологические подходы, которые не убедили основную политологию,[2] имеет очень "мало консенсуса по определяющим принципам, таким как определение геноцида, типология, применение сравнительного метода и временные рамки".[3][f] По мнению профессора экономики Аттиата Отта, массовое убийство стало "более простым" термином.[g] Поскольку сравнительных исследований по коммунистическим режимам мало или вообще нет, не удалось достичь академического консенсуса относительно причин и определения таких убийств в более или менее широких, общих терминах. Исследователи геноцида не придавали особого значения типу режима при проведении сравнительного анализа,[4] который применялся в нескольких случаях, ограниченных лишь Советским Союзом при Иосифе Сталине, Китаем при Мао Цзэдуне,[5] и Камбоджей при Пол Поте[6] на том основании, что Сталин повлиял на Мао, который повлиял на Пол Пота; в этих случаях убийства совершались как часть политики несбалансированного процесса быстрой индустриализаци.[7]

Несколько авторов пытались предложить общую терминологию для описания убийств безоружных гражданских лиц коммунистическими правительствами, по отдельности или в целом, некоторые из них считают, что политика правительства, интересы, пренебрежение и бесхозяйственность прямо или косвенно способствовали таким убийствам, и оценивают различные причины смерти, которые определяются различными терминами. Согласно этой точке зрения, которая либо игнорируется, либо критикуется другими исследователями геноцида и исследователями коммунизма, можно получить оценку числа погибших от коммунизма на основе группировки "общий коммунизм". Критики коммунизма определяют категорию "общий коммунизм" как любое движение политической партии, возглавляемое интеллектуалами; этот зонтичный термин позволяет объединить такие разные режимы, как радикальный советский индустриализм и антиурбанизм "красных кхмеров".[8]

Общие или заметные термины, используемые авторами, не все из которых могут разделять признание группировки "общий коммунизм", включают следующие:[g]

- Классицид — Социолог Майкл Манн предложил классицид для обозначения "намеренного массового убийства целых социальных классов".[h] Как резюмирует Онлайн-энциклопедия массового насилия, классицид считается "преднамеренным массовым убийством", более узким, чем геноцид, поскольку он направлен на часть населения, определяемую его социальным статусом, но более широким, чем политицид, поскольку группа становится мишенью без учета ее политической активности.[9]

- Преступления против человечности — профессор истории Клас-Гёран Карлссон использует термин "преступления против человечности", который включает "прямые массовые убийства политически нежелательных элементов, а также насильственные депортации и принудительный труд". Карлссон утверждает, что этот термин может ввести в заблуждение в том смысле, что режимы выбирали в качестве мишени группы своих собственных граждан, но считает его полезным в качестве широкого юридического термина, который подчеркивает нападения на гражданское население, а также потому, что эти преступления унижают человечество в целом.[10] Манн и историк Жак Семелин[11] считают, что преступление против человечности более уместно, чем геноцид или политическое убийство, когда речь идет о насилии со стороны коммунистических режимов.[12]

- Демоцид — политолог Рудольф Руммель определил демоцид как "преднамеренное убийство безоружного или обезоруженного человека правительственными агентами, действующими в своем авторитетном качестве и в соответствии с политикой правительства или высшего командования".[13] Его определение охватывает широкий спектр смертей, включая жертв принудительных работ и концентрационных лагерей, убийства неофициальными частными группами, внесудебные суммарные убийства, массовые смерти вследствие правительственных актов преступного бездействия и пренебрежения, таких как преднамеренный голод, а также убийства, совершаемые правительствами де-факто, такими как военачальники или повстанцы в гражданской войне.[14][i] Это определение охватывает любое убийство любого количества людей любым правительством,[15] и оно было применено к убийствам, совершенным коммунистическими режимами.[16][17]

- Геноцид — Согласно Конвенции о геноциде, преступление геноцида обычно применяется к массовому убийству этнических, а не политических или социальных групп. Пункт, предоставляющий защиту политическим группам, был исключен из резолюции ООН после повторного голосования, поскольку многие государства, включая Советский Союз при Сталине,[18][j] опасались, что он может быть использован для наложения ненужных ограничений на их право подавлять внутренние беспорядки.[19][20] Научные исследования геноцида обычно признают, что ООН не учитывает экономические и политические группы, и используют данные о массовых политических убийствах - демоциде, геноциде и политициде или генополитициде.[21] Убийства, совершенные "красными кхмерами" в Камбодже, были названы геноцидом или автогеноцидом, а смерти, произошедшие при ленинизме и сталинизме в Советском Союзе, а также смерти, произошедшие при маоизме в Китае, были неоднозначно расследованы как возможные случаи. В частности, советский голод 1932-1933 годов и Великий китайский голод, который произошел во время Великого скачка вперед, "изображались как случаи массовых убийств, подкрепленных геноцидными намерениями".[k]

- Холокост — коммунистический холокост используется некоторыми государственными деятелями и неправительственными организациями.[22][23][24] Аналогичное название "Холокост", придуманное Мюнхенским институтом истории,[l][25] профессор сравнительных экономических систем Стивен Роузфилд использовал для коммунистических "государственных убийств в мирное время", заявив при этом, что оно "может быть определено как включающее все убийства (санкционированные судом террористические казни), уголовные убийства (смертоносные принудительные работы и этнические чистки) и убийства по неосторожности (террор-голодовка), произошедшие в результате мятежных действий и гражданских войн до захвата государства, а также все последующие уголовные государственные убийства".[m] По словам историка Йорга Хакмана, такие термины не пользуются популярностью среди ученых ни в Германии, ни за рубежом.[l] Историк Александра Линьель-Лавастин пишет, что использование этих терминов "позволяет реальности, которую они описывают, немедленно обрести в западном сознании статус, равный статусу уничтожения евреев нацистским режимом".[n][26] Политолог Майкл Шафир пишет, что использование таких терминов поддерживает "конкурентный компонент мученичества двойного геноцида", теорию, худшей версией которой является обфускация Холокоста.[27] Джордж Войку утверждает, что коллега-историк Леон Воловичи "справедливо осудил злоупотребление этим понятием как попытку "узурпировать" и подорвать символ, характерный для истории европейских евреев".[o]

- Массовое убийство — профессор психологии Эрвин Стауб определил массовое убийство как "убийство членов группы без намерения уничтожить всю группу или убийство большого количества людей без точного определения принадлежности к группе. При массовом убийстве число убитых обычно меньше, чем при геноциде".[28][p] Ссылаясь на более ранние определения,[q] профессора Джоан Эстебан (экономический анализ), Массимо Морелли (политология и экономика) и Доминик Ронер (политическая и институциональная экономика) определили массовые убийства как "убийства значительного числа людей, когда они совершаются не в ходе военных действий против вооруженных сил явного противника, в условиях существенной беззащитности и беспомощности жертв".[29] Массовое убийство было определено политологом Бенджамином Валентино как "преднамеренное убийство массового числа некомбатантов", где "массовое число" определяется как не менее 50 000 преднамеренных смертей в течение пяти лет или менее.[30] Это наиболее принятый количественный минимальный порог для данного термина;[29] Валентино применил это определение к случаям Советского Союза эпохи Сталина, Китая эпохи Мао и Камбоджи времен красных кхмеров, и попытался объяснить, почему многие другие коммунистические режимы избежали "такого уровня насилия", комментируя, что "большинство режимов, которые называли себя коммунистическими или были названы таковыми другими, не занимались массовыми убийствами", и не смог подтвердить или проверить, подходят ли под категорию массовых убийств "массовые убийства меньшего масштаба", которые, судя по всему, также совершались режимами в различных странах Африки, Восточной Европы, Северной Кореи, Вьетнама и других союзников СССР.[31] Политолог Джей Улфелдер использует порог в 1 000 убитых.[r] Профессор кафедры изучения мира и конфликтов Алекс Дж. Беллами утверждает, что 14 из 38 случаев "массовых убийств с 1945 года, совершенных недемократическими государствами вне контекста войны", были совершены коммунистическими правительствами.[s] Профессор международных отношений Ацуси Таго и профессор политологии Фрэнк Уэйман использовали массовые убийства из Валентино и прокомментировали, что даже при более низком пороге (10 000 убитых в год, 1 000 убитых в год или всего 1 убитый в год), "автократические режимы, особенно коммунистические, склонны к массовым убийствам в целом, но не так сильно склонны (т.е. статистически значимо не склонны) к генополитициду".[t] По мнению профессора экономики Аттиата Ф. Отта и его постдокторанта Санг Ху Бэ, существует общее мнение, что массовое убийство представляет собой акт намеренного убийства некоторого количества некомбатантов, но это количество может варьироваться от всего лишь четырех до более чем 50 000 человек.[32] Доцент социологии Ян Су использует определение массового убийства, данное Валентино, но допускает в качестве "значительного числа" более 10 убитых за один день в одном городе.[u] Янг использовал коллективное убийство для анализа массовых убийств на территориях меньше целой страны, которые могут не соответствовать порогу Валентино.[v]

- Политицид — Этот термин используется для описания убийства групп, которые в противном случае не подпадали бы под действие Конвенции о геноциде.[33][j] Исследователь геноцида Барбара Харфф изучает геноцид и политицид — иногда сокращенно генополицид — для того, чтобы включить убийства политических, экономических, этнических и культурных групп.[w] Политолог Манус И. Мидларски использует политицид для описания дуги крупномасштабных убийств от западных районов Советского Союза до Китая и Камбоджи.[x] В своей книге "Убийственная ловушка: геноцид в двадцатом веке" Мидларски отмечает сходство между убийствами Сталина и Пол Пота.[34]

- Репрессии — Советский специалист Стивен Уиткрофт утверждает, что в случае с Советским Союзом такие термины, как террор, чистки и репрессии, используются для обозначения одних и тех же событий. Уиткрофт считает, что наиболее нейтральными терминами являются репрессии и массовые убийства, хотя в русском языке широкое понятие репрессий обычно включает в себя массовые убийства и иногда считается их синонимом, чего нельзя сказать о других языках.[35]

Попытка оценок

По словам Класа-Горана Карлссона, обсуждение количества жертв коммунистических режимов было "чрезвычайно обширным и идеологически предвзятым".[7] Рудольф Руммель и Марк Брэдли написали, что, хотя точные цифры были предметом спора, порядок величины не является таковым.[y][z] Руммель и другие исследователи геноцида сосредоточены в первую очередь на установлении закономерностей и проверке различных теоретических объяснений геноцидов и массовых убийств. В своей работе, поскольку они имеют дело с большими массивами данных, описывающих события массовой смертности в глобальном масштабе, им приходится полагаться на выборочные данные, предоставленные экспертами по странам, поэтому точные оценки не являются ни требуемым, ни ожидаемым результатом их работы.[36]

Любая попытка оценить общее количество убийств при коммунистических режимах сильно зависит от определений, а идея объединить разные страны, такие как Афганистан и Венгрия, не имеет адекватного объяснения.[37] В эпоху холодной войны некоторые авторы (Тодд Калберстон), диссиденты (Александр Солженицын) и антикоммунисты в целом пытались провести как страновые, так и глобальные оценки, хотя они были в основном ненадежными и завышенными, как показали 1990-е годы и последующие годы. Исследователи коммунизма в основном фокусировались на отдельных странах, а исследователи геноцида пытались представить более глобальную перспективу, утверждая при этом, что их цель — не достоверность, а установление закономерностей.[36] Ученые, изучающие коммунизм, спорили об оценках для Советского Союза, а не для всех коммунистических режимов, попытка, которая была популяризирована введением к "Черной книге коммунизма" и вызвала споры.[37] Среди них советские специалисты Майкл Эллман и Дж. Арч Гетти критиковали эти оценки за то, что они полагаются на эмигрантские источники, слухи и сплетни в качестве доказательств,[38] и предупреждали, что историкам следует использовать архивные материалы.[39] Такие ученые проводят различие между историками, которые основывают свои исследования на архивных материалах, и теми, чьи оценки основаны на свидетельствах очевидцев и других данных, которые являются ненадежными.[40] Советский специалист Стивен Г. Уиткрофт говорит, что историки полагались на Солженицына, чтобы поддержать свои более высокие оценки, но исследования в государственных архивах подтвердили более низкие оценки, добавляя при этом, что в популярной прессе продолжают появляться серьезные ошибки, которые не следует цитировать или полагаться на них в научных кругах.[41] Руммель также является еще одним широко используемым и цитируемым источником,[aa] но не надежным в отношении оценок.[36]

Среди известных попыток оценки можно отметить следующие:[aa]

- В 1978 году журналист Тодд Калбертсон написал статью в The Richmond News Leader, переизданную в Human Events, в которой он заявил, что "[имеющиеся данные] указывают на то, что, возможно, 100 миллионов человек были уничтожены коммунистами; непроницаемость железных и бамбуковых занавесов не позволяет назвать более точную цифру".[ab][aa]

- В 1985 году Джон Ленчовски, директор по европейским и советским делам в Совете национальной безопасности США, написал статью в "The Christian Science Monitor", в которой заявил, что "число людей, убитых коммунистическими режимами, оценивается от 60 до 150 миллионов, причем более высокая цифра, вероятно, является более точной в свете последних исследований".[ac]

- В 1993 году Збигнев Бжезинский, бывший советник по национальной безопасности Джимми Картера, написал, что "неудачные попытки построить коммунизм в двадцатом веке унесли жизни почти 60 000 000 человек".[42][aa][ad]

- В 1994 году в книге Руммеля "Смерть от правительства" было указано около 110 миллионов человек, иностранных и отечественных, убитых в результате коммунистического демоцида с 1900 по 1987 год.[43] В это общее число не вошли смерти от Великого китайского голода 1958-1961 годов из-за тогдашнего убеждения Руммеля, что "хотя политика Мао была ответственна за голод, он был введен в заблуждение относительно этого, и в конце концов, когда он узнал об этом, он остановил его и изменил свою политику".[44][45] В 2004 году Томислав Дулич раскритиковал оценку Руммелем числа убитых в Югославии Тито как завышенную, основанную на включении низкокачественных источников, и заявил, что другие оценки Руммеля могут страдать от той же проблемы, если он использовал для них аналогичные источники.[46] В ответ Руммель выступил с критикой анализа Дулича,[47] но она не была убедительной.[48] В 2005 году отставной Руммель пересмотрел в сторону увеличения свое общее число жертв коммунистического демоцида между 1900 и 1999 годами со 110 миллионов до примерно 148 миллионов в связи с дополнительной информацией о виновности Мао в Великом китайском голоде из книги "Мао: The Unknown Story, включая оценку Джона Холлидея и Джунг Чанга в 38 миллионов жертв голода.[44][45] Карлссон описывает оценки Руммеля как находящиеся на периферии, заявляя, что "они вряд ли являются примером серьезного и эмпирически обоснованного написания истории", и в основном обсуждает их "на основе интереса к нему в блогосфере".[49]

- В 1997 году Стефан Куртуа во введении к "Черной книге коммунизма", впечатляющей, но противоречивой[37] работе, написанной об истории коммунизма в 20 веке,[50] привел "приблизительную цифру, основанную на неофициальных оценках", приближающуюся к 100 миллионам убитых. Суммарные итоги, перечисленные Куртуа, составили 94,36 млн. убитых.[ae] Николя Верт и Жан-Луи Марголин, соавторы книги, критикуют Куртуа, считая его одержимым стремлением достичь 100-миллионного общего показателя.[51] В своем предисловии к английскому изданию 1999 года Мартин Малиа написал, что "общее число жертв, по разным оценкам авторов этого тома, составляет от 85 до 100 миллионов".[af] Попытка Куртуа приравнять нацизм и коммунистические режимы была спорной и остается на задворках как с научной, так и с моральной точки зрения.[52][ag]

- В 2005 году Бенджамин Валентино заявил, что число некомбатантов, убитых коммунистическими режимами только в Советском Союзе, Китае и Камбодже, варьировалось от 21 миллиона до 70 миллионов.[ah][ai] Ссылаясь на Руммеля и других,[aa] Валентино пишет, что "самый высокий предел правдоподобного диапазона смертей, приписываемых коммунистическим режимам", составляет до 110 миллионов".[ah]

- В 2010 году Стивен Роузфилд, основная мысль которого заключается в том, что коммунизм в целом, хотя он в основном фокусируется на сталинизме, менее геноциден, и это является ключевым отличием от нацизма, написал в книге "Красный холокост", что внутренние противоречия коммунистических режимов стали причиной убийства примерно 60 миллионов человек и, возможно, десятков миллионов других.[53]

- В 2011 году Мэтью Уайт опубликовал приблизительную цифру в 70 миллионов "людей, погибших при коммунистических режимах от казней, трудовых лагерей, голода, этнических чисток и отчаянного бегства на дырявых лодках", не считая погибших в войнах.[aj]

- В 2012 году Алекс Дж. Беллами написал, что "по консервативным оценкам общее число гражданских лиц, преднамеренно убитых коммунистами после Второй мировой войны, составляет от 6,7 млн до 15,5 млн человек, причем истинная цифра, вероятно, гораздо выше".[ak]

- В 2014 году Джулия Штраус написала, что в то время как в научных кругах начали приходить к консенсусу относительно цифр в 20 миллионов убитых в Советском Союзе и 2-3 миллиона в Камбодже, в отношении Китая такого консенсуса нет.[al]

- В 2016 году блог "Диссидент" Фонда памяти жертв коммунизма предпринял попытку собрать диапазоны оценок, используя источники с 1976 по 2010 год, утверждая, что общий диапазон "колеблется от 42 870 000 до 161 990 000" убитых, а наиболее часто упоминаемая цифра — 100 миллионов..[am]

- В 2017 году Стивен Коткин написал в The Wall Street Journal, что коммунистические режимы убили не менее 65 миллионов человек в период с 1917 по 2017 год, прокомментировав это: "Хотя коммунизм убил огромное количество людей намеренно, еще больше его жертв умерло от голода в результате его жестоких проектов социальной инженерии".[54][an]

Критика в основном сосредоточена на трех аспектах, а именно: оценки основаны на скудных и неполных данных, когда неизбежны значительные ошибки,[55][56][57] цифры перекошены в сторону более высоких возможных значений,[55][58][ao] а жертвы гражданских войн, Голодомора и других голодов, а также войн с участием коммунистических правительств не должны учитываться.[55][59][60] Критика высоких оценок, таких как оценки Руммеля, сосредоточена на двух аспектах, а именно на выборе источников данных и статистическом подходе. Исторические источники, на которых Руммель основывал свои оценки, редко могут служить источником достоверных цифр.[61] Статистический подход, который Руммель использовал для анализа больших наборов разнообразных оценок, может привести к разбавлению полезных данных шумными.[61][62]

Другая распространенная критика, сформулированная антропологом и специалистом по бывшим европейским коммунистическим режимам Кристен Годзее и другими учеными, заключается в том, что подсчет тел отражает антикоммунистическую точку зрения и в основном используется антикоммунистическими учеными, и является частью популярного нарратива о "жертвах коммунизма",[63][64] причем 100 миллионов — наиболее распространенная, популярная оценка,[65][ap] которая используется не только для дискредитации коммунистического движения, но и всех политических левых.[66][aq] Антикоммунистические организации стремятся институционализировать нарратив "жертв коммунизма" в качестве теории двойного геноцида, или моральной эквивалентности между нацистским Холокостом (убийство расы) и теми, кого убили коммунистические режимы (убийство класса).[63][67] Наряду с философом Скоттом Сехоном, Годси писал, что "спорить о цифрах неприлично. Важно то, что многие, очень многие люди были убиты коммунистическими режимами".[67] Такой же подсчет трупов можно легко применить и к другим идеологиям или системам, например, к капитализму.[65][ar][67][as]

Предполагаемые причины

Идеология

Клас-Гёран Карлссон пишет: "Идеологии — это системы идей, которые не могут совершать преступления самостоятельно. Однако отдельные лица, коллективы и государства, определявшие себя как коммунистические, совершали преступления во имя коммунистической идеологии или не называя коммунизм в качестве прямого источника мотивации своих преступлений".[68] Такие ученые, как Рудольф Руммель, Даниэль Голдхаген,[69] Ричард Пайпс[70] и Джон Грей[71] считают идеологию коммунизма важным причинным фактором массовых убийств.[55][72] Во введении к "Черной книге коммунизма" Стефан Куртуа утверждает связь между коммунизмом и преступностью, заявляя, что "коммунистические режимы... превратили массовую преступность в полноценную систему управления,[73] добавляя при этом, что эта преступность лежит на уровне идеологии, а не государственной практики.[74]

Профессор Марк Брэдли пишет, что коммунистическая теория и практика часто находилась в противоречии с правами человека, и большинство коммунистических государств следовали примеру Карла Маркса, отвергая "неотъемлемые индивидуальные политические и гражданские права эпохи Просвещения" в пользу "коллективных экономических и социальных прав".[z] Кристофер Дж. Финлей утверждает, что марксизм узаконивает насилие без каких-либо четких ограничивающих принципов, потому что он отвергает моральные и этические нормы как конструкты господствующего класса, и заявляет, что "вполне мыслимо, чтобы революционеры совершали жестокие преступления в процессе установления социалистической системы, веря, что их преступления будут задним числом отпущены новой системой этики, созданной пролетариатом".[at] Рустам Сингх утверждает, что Маркс намекал на возможность мирной революции; после неудачной революции 1848 года Сингх утверждает, что Маркс подчеркивал необходимость насильственной революции и революционного террора.[au]

Историк литературы Джордж Уотсон процитировал статью Фридриха Энгельса "Венгерская борьба", написанную в 1849 году и опубликованную в журнале Маркса "Neue Rheinische Zeitung", заявив, что труды Энгельса и других показывают, что "марксистская теория истории требовала и требует геноцида по причинам, скрытым в ее утверждении, что феодализм, который в передовых странах уже уступает место капитализму, должен в свою очередь быть вытеснен социализмом. После революции рабочих останутся целые народы, феодальные пережитки в эпоху социализма, и поскольку они не могут продвинуться на два шага вперед, их придется убить. Они были расовым мусором, как назвал их Энгельс, и годились только для мусорной кучи истории".[75][av] Утверждения Уотсона подверглись критике за сомнительные доказательства со стороны Роберта Гранта, который заметил, что "то, к чему призывают Маркс и Энгельс, является ... по меньшей мере, своего рода культурным геноцидом; но не очевидно, по крайней мере, из цитат Уотсона, что речь идет о реальном массовом убийстве, а не (используя их фразеологию) простом "поглощении" или "ассимиляции"".[76] Говоря о статье Энгельса 1849 года, историк Анджей Валицкий заявляет: "Трудно отрицать, что это был откровенный призыв к геноциду".[77] Жан-Франсуа Ревель пишет, что Иосиф Сталин рекомендовал изучить статью Энгельса 1849 года в своей книге "О Ленине и ленинизме" в 1924 году.[aw]

По мнению Руммеля, убийства, совершенные коммунистическими режимами, лучше всего можно объяснить как результат брака между абсолютной властью и абсолютистской идеологией марксизма.[78] Руммель утверждает, что "коммунизм был похож на фанатичную религию. У него был свой открытый текст и свои главные толкователи. У него были свои священники и их ритуальная проза со всеми ответами. У него были небеса и правильное поведение, чтобы достичь их. Она призывала к вере. И у нее были крестовые походы против неверующих. Что делало эту светскую религию столь смертоносной, так это захват всех государственных инструментов силы и принуждения и их немедленное использование для уничтожения или контроля всех независимых источников власти, таких как церковь, профессии, частный бизнес, школы и семья".[79] Руммельс пишет, что марксистские коммунисты рассматривали строительство своей утопии как "хотя и войну с бедностью, эксплуатацией, империализмом и неравенством. И ради высшего блага, как и в настоящей войне, убивают людей. И, таким образом, эта война за коммунистическую утопию имела свои необходимые вражеские жертвы, духовенство, буржуазию, капиталистов, разрушителей, контрреволюционеров, правых, тиранов, богачей, помещиков и некомбатантов, которые, к сожалению, попали в бой. В войне могут погибнуть миллионы, но причина может быть вполне оправданной, как в случае с поражением Гитлера и абсолютно расистского нацизма. А для многих коммунистов дело коммунистической утопии было таким, что оправдывало все смерти".[78]

Бенджамин Валентино пишет, что "очевидно высокий уровень политической поддержки убийственных режимов и лидеров не должен автоматически приравниваться к поддержке массовых убийств как таковых. Люди способны поддерживать жестокие режимы или лидеров, оставаясь безразличными или даже выступая против конкретной политики, проводимой этими режимами". Валентино приводит слова Владимира Бровкина о том, что "голосование за большевиков в 1917 году не было голосованием за красный террор или даже голосованием за диктатуру пролетариата".[80] По мнению Валентино, такие стратегии были столь жестокими, потому что они экономически лишали права собственности большое количество людей,[ax][s] комментируя это: "Социальные преобразования такой скорости и масштаба были связаны с массовыми убийствами по двум основным причинам. Во-первых, массовые социальные потрясения, вызванные такими изменениями, часто приводили к экономическому коллапсу, эпидемиям и, что самое важное, широкомасштабному голоду. ... Вторая причина, по которой коммунистические режимы, стремящиеся к радикальной трансформации общества, были связаны с массовыми убийствами, заключается в том, что революционные изменения, которые они проводили, вступали в неумолимое столкновение с фундаментальными интересами больших слоев населения. Мало кто оказался готов пойти на такие далеко идущие жертвы без сильного принуждения". По словам Жака Семелина, "коммунистические системы, возникшие в двадцатом веке, в конечном итоге уничтожили свое собственное население, но не потому, что планировали уничтожить его как таковое, а потому, что стремились перестроить "социальное тело" сверху донизу, даже если это означало его чистку и перекройку в соответствии с их новым прометеевским политическим воображением".[ay]

Дэниел Чирот и Кларк Макколи пишут, что, особенно в Советском Союзе Иосифа Сталина, Китае Мао Цзэдуна и Камбодже Пол Пота, фанатичная уверенность в том, что социализм можно заставить работать, мотивировала коммунистических лидеров на "безжалостное обесчеловечивание своих врагов, которых можно было подавить, потому что они были "объективно" и "исторически" неправы". Более того, если события развивались не так, как предполагалось, то это происходило потому, что классовые враги, иностранные шпионы и диверсанты или, что хуже всего, внутренние предатели разрушали план. Ни при каких обстоятельствах нельзя было признать, что сама концепция может оказаться невыполнимой, потому что это означало капитуляцию перед силами реакции".[az] Майкл Манн пишет, что члены коммунистической партии были "идеологически мотивированы, считая, что для создания нового социалистического общества они должны вести за собой социалистическое рвение. Убийства часто были популярны, рядовые члены партии стремились перевыполнить квоты на убийства, как и квоты на производство".[ba] По словам Владимира Тисманяну, "коммунистический проект в таких странах, как СССР, Китай, Куба, Румыния или Албания, был основан именно на убеждении, что определенные социальные группы являются необратимо чуждыми и заслуженно убитыми".[bb] Алекс Беллами пишет, что "коммунистическая идеология выборочного уничтожения" целевых групп была впервые разработана и применена Иосифом Сталиным, но "каждый из коммунистических режимов, уничтоживших большое количество гражданских лиц во время холодной войны, разработал свой собственный отличительный счет",[bc] а Стивен Т. Кац утверждает, что различия на основе класса и национальности, стигматизированные и стереотипизированные различными способами, создали "инаковость" для жертв коммунистического правления, что было важно для легитимации угнетения и смерти.[bd] Мартин Шоу пишет, что "националистические идеи лежали в основе многих массовых убийств в коммунистических государствах", начиная с "новой националистической доктрины Сталина о "социализме в одной стране"", а убийства революционными движениями в странах третьего мира совершались во имя национального освобождения.[be]

Политическая система

Энн Эпплбаум пишет, что "без исключения ленинская вера в однопартийное государство была и остается характерной для каждого коммунистического режима", а "большевистское применение насилия повторялось в каждой коммунистической революции". Фразы, сказанные Владимиром Лениным и основателем ЧК Феликсом Дзержинским, были распространены по всему миру. Эпплбаум утверждает, что еще в 1976 году Менгисту Хайле Мариам развязал красный террор в Эфиопии.[81] Ленин, обращаясь к своим коллегам по большевистскому правительству, сказал: "Если мы не готовы расстрелять саботажника и белогвардейца, то что же это за революция?".[82]

Роберт Конквест подчеркнул, что сталинские чистки не противоречили принципам ленинизма, а скорее были естественным следствием системы, созданной Лениным, который лично отдавал приказы об убийстве локальных групп заложников классового врага.[83] Александр Николаевич Яковлев, архитектор перестройки и гласности, впоследствии глава Комиссии при Президенте РФ по делам жертв политических репрессий, развивает эту мысль, заявляя: "Правда в том, что в карательных операциях Сталин не придумал ничего такого, чего не было бы при Ленине: казни, захват заложников, концлагеря и все остальное".[84] Историк Роберт Геллати согласен с этим, комментируя: "Говоря по-другому, Сталин инициировал очень мало того, что Ленин уже не ввел или не предвосхитил".[85]

Стивен Хикс из Рокфордского колледжа приписывает насилие, характерное для социалистического правления 20-го века, отказу этих коллективистских режимов от защиты гражданских прав и неприятию ценностей гражданского общества. Хикс пишет, что в то время как "на практике каждая либеральная капиталистическая страна имеет солидный послужной список гуманности, уважения прав и свобод и возможности для людей строить плодотворную и осмысленную жизнь", при социализме "практика снова и снова доказывает, что она более жестока, чем худшие диктатуры до двадцатого века. Каждый социалистический режим рушился в диктатуру и начинал убивать людей в огромных масштабах."[86]

Эрик Д. Вайц утверждает, что массовые убийства в коммунистических государствах являются естественным следствием провала верховенства закона, что обычно наблюдается в периоды социальных потрясений в 20 веке. Что касается как коммунистических, так и некоммунистических массовых убийств, "геноциды происходили в моменты крайнего социального кризиса, часто порожденного самой политикой режимов",[87] и не являются неизбежными, а представляют собой политические решения.[87] Стивен Роузфилд пишет, что коммунистическим правителям приходилось выбирать между сменой курса и "террор-командованием", и чаще всего они выбирали последнее.[bf] Майкл Манн считает, что отсутствие институционализированных структур власти означало, что хаотичное сочетание централизованного контроля и партийной фракционности были факторами убийства.[ba]

Лидеры

Профессор Мэтью Крайн утверждает, что многие ученые указывают на революции и гражданские войны как на возможность для радикальных лидеров и идеологий получить власть и предпосылки для массовых убийств со стороны государства.[bg] Профессор Нам Кю Ким пишет, что идеология исключения имеет решающее значение для объяснения массовых убийств, но организационные возможности и индивидуальные характеристики революционных лидеров, включая их отношение к риску и насилию, также важны. Помимо того, что революции открывают перед новыми лидерами политические возможности для устранения своих политических оппонентов, они приводят к власти лидеров, которые более склонны совершать масштабные акты насилия против гражданского населения для легитимизации и укрепления собственной власти.[88] Исследователь геноцида Адам Джонс утверждает, что Гражданская война в России оказала большое влияние на появление таких лидеров, как Сталин, а также приучила людей к "суровости, жестокости, террору".[bh] Мартин Малиа назвал "жестокую обусловленность" двух мировых войн важной для понимания коммунистического насилия, хотя и не его источника.[89]

Историк Хелен Раппапорт описывает Николая Ежова, бюрократа, возглавлявшего НКВД во время Великой чистки, как физически миниатюрную фигуру с "ограниченным интеллектом" и "узким политическим пониманием". ... Как и другие зачинщики массовых убийств на протяжении всей истории, [он] компенсировал недостаток физического роста патологической жестокостью и применением грубого террора".[90] Исследователь русской и мировой истории Джон М. Томпсон возлагает личную ответственность непосредственно на Иосифа Сталина. По его словам, "многое из того, что произошло, имеет смысл только в том случае, если оно частично проистекает из нарушенной психики, патологической жестокости и крайней паранойи самого Сталина. Неуверенный в себе, несмотря на установление диктатуры над партией и страной, враждебный и оборонительный, когда его критиковали за излишества коллективизации и жертвы, которых требовала высокотемповая индустриализация, и глубоко подозревавший, что прошлые, настоящие и даже еще неизвестные будущие противники готовят против него заговор, Сталин начал вести себя как человек, попавший в осаду. Вскоре он нанес ответный удар по врагам, реальным или воображаемым".[91] Профессора Пабло Монтаньес и Стефан Вольтон утверждают, что чистки в Советском Союзе и Китае можно объяснить персоналистским руководством Сталина и Мао, которые были стимулированы как контролем над аппаратом безопасности, используемым для проведения чисток, так и контролем над назначением замен для тех, кого чистили.[bi] Словенский философ Славой Жижек объясняет то, что Мао якобы рассматривал человеческую жизнь как одноразовую, его "космическим взглядом" на человечество.[bj]

По государству

Советский Союз

Адам Джонс пишет, что "в истории человечества мало что может сравниться с насилием, которое было развязано в период с 1917 года, когда к власти пришли большевики, до 1953 года, когда умер Иосиф Сталин и Советский Союз перешел к более сдержанной и в основном не убийственной внутренней политике". Джонс утверждает, что исключение составляют красные кхмеры (в относительном выражении) и правление Мао в Китае (в абсолютном выражении).[92]

Стивен Дж. Уиткрофт говорит, что до открытия советских архивов для исторических исследований "наше понимание масштабов и характера советских репрессий было крайне скудным", и что некоторым ученым, желающим сохранить высокие оценки до 1991 года, "трудно адаптироваться к новым обстоятельствам, когда архивы открыты и когда есть множество неопровержимых данных", и вместо этого "держатся за свои старые советологические методы с окольными путями расчетов, основанных на странных заявлениях эмигрантов и других информаторов, которые, как предполагается, обладают высшими знаниями", хотя он признал, что даже цифры, оцененные на основе дополнительных документов, не являются "окончательными или окончательными".[93][94] В пересмотренном в 2007 году издании своей книги "Большой террор" Роберт Конквест считает, что, хотя точные цифры никогда не будут определены, коммунистические лидеры Советского Союза несут ответственность не менее чем за 15 миллионов смертей.[bk]

Некоторые историки пытаются сделать отдельные оценки для различных периодов советской истории, при этом оценки потерь сильно варьируются от 6 миллионов (сталинский период)[95] до 8,1 миллиона (конец 1937 года)[96] и от 20 миллионов[73][bl] до 61 миллиона (период 1917-1987 годов).[97]

Красный террор

Красный террор — это период политических репрессий и казней, проведенных большевиками после начала Гражданской войны в России в 1918 году. В этот период политическая полиция (ЧК) провела бессудные казни десятков тысяч "врагов народа".[98][99][100][101][102] Многие жертвы были "буржуазными заложниками", которых собирали и держали наготове для расстрела в отместку за любую предполагаемую контрреволюционную провокацию.[103] Многие были преданы смерти во время и после подавления восстаний, таких как Кронштадтское восстание моряков Балтийского флота и Тамбовское восстание русских крестьян. Профессор Дональд Рейфилд пишет, что "репрессии, последовавшие за восстаниями только в Кронштадте и Тамбове, привели к десяткам тысяч казней".[104] Также было убито большое количество православных священнослужителей.[105][106]

По мнению Николаса Верта, политика раскулачивания была попыткой советских лидеров "ликвидировать, истребить и депортировать население целой территории".[107] В первые месяцы 1919 года, возможно, от 10 000 до 12 000 казаков были казнены[108][109] и еще больше депортированы после того, как их станицы были стерты с лица земли.[110] Историк Майкл Корт писал: "В течение 1919 и 1920 годов из примерно 1,5 миллиона донских казаков большевистский режим убил или депортировал от 300 000 до 500 000 человек".[111]

Иосиф Сталин

Оценки количества смертей, вызванных правлением Сталина, горячо обсуждаются учеными в области советских и коммунистических исследований.[112][113] До распада Советского Союза и последовавших за ним архивных разоблачений некоторые историки считали, что число людей, убитых сталинским режимом, составляло 20 миллионов или больше.[95][114][115] Майкл Паренти пишет, что оценки числа погибших при сталинской власти сильно разнятся отчасти потому, что такие оценки основаны на анекдотах в отсутствие достоверных свидетельств и "предположениях авторов, которые никогда не раскрывают, как они пришли к таким цифрам".[116]

После распада Советского Союза стали доступны свидетельства из советских архивов, содержащие официальные записи о казни около 800 000 заключенных при Сталине за политические или уголовные преступления, около 1,7 миллиона смертей в ГУЛАГах и около 390 000 смертей, произошедших во время принудительных поселений кулаков в Советском Союзе, в общей сложности около 3 миллионов официально зарегистрированных жертв в этих категориях.[bm] По мнению Гольфо Алексопулоса, Энн Эпплбаум, Олега Хлевнюка и Майкла Эллмана, официальная советская документация о смертях в ГУЛАГе считается неадекватной, поскольку, как они пишут, правительство часто освобождало заключенных на грани смерти, чтобы избежать их официального подсчета.[117][118] Исследование архивных данных, проведенное в 1993 году Дж. Арчем Гетти и др. показало, что в общей сложности 1 053 829 человек умерли в ГУЛАГе с 1934 по 1953 год.[119] В 2010 году Стивен Роузфилд заявил, что это число должно быть увеличено на 19,4 процента в свете более полных архивных данных до 1 258 537 человек, а наилучшая оценка смертей в ГУЛАГе составляет 1,6 миллиона с 1929 по 1953 год, если учитывать избыточную смертность.[120] Алексополус считает, что общее число умерших в ГУЛАГе или вскоре после освобождения гораздо выше — не менее 6 миллионов человек.[121] Дэн Хили назвал ее работу "вызовом формирующемуся научному консенсусу",[bn] а Джеффри Харди раскритиковал Алексопулос за то, что она основывает свои утверждения в основном на косвенных и неверно истолкованных доказательствах.[122]

По мнению историка Стивена Г. Уиткрофта, сталинский режим можно обвинить в целенаправленной гибели около миллиона человек.[123] Уиткрофт исключает все случаи смерти от голода как целенаправленные смерти и считает, что те, которые подпадают под категорию казни, а не убийства.[123] Другие утверждают, что некоторые действия сталинского режима, не только во время Голодомора, но и декулакизация и целенаправленные кампании против определенных этнических групп, такие как польская операция НКВД, могут рассматриваться как геноцид,[124][125] по крайней мере, в его свободном определении.[126] Современные данные за весь период правления Сталина были обобщены Тимоти Снайдером, который заявил, что при сталинском режиме было шесть миллионов прямых смертей и девять миллионов общих, включая смерть от депортации, голода и смертей в ГУЛАГе.[bo] Эллман приписывает сталинскому режиму примерно 3 миллиона смертей, не считая избыточной смертности от голода, болезней и войны.[127] Несколько авторов популярной прессы, среди которых биограф Сталина Саймон Себаг Монтефиоре, советский/российский историк Дмитрий Волкогонов и директор йельской серии "Анналы коммунизма" Джонатан Брент, по-прежнему называют число погибших от рук Сталина около 20 миллионов человек.[bp][bq][br][bs][bt]

Массовые депортации национальных меньшинств

Советское правительство во время правления Сталина провело серию депортаций огромного масштаба, которые существенно повлияли на этническую карту Советского Союза. Депортации проходили в чрезвычайно суровых условиях, часто в вагонах для скота, сотни тысяч депортированных умирали в пути.[128] По оценкам некоторых экспертов, доля смертей в результате депортаций может достигать одного к трем в определенных случаях.[bu][129] Рафаэль Лемкин, юрист польско-еврейского происхождения, инициатор Конвенции о геноциде 1948 года и сам придумавший термин геноцид, предположил, что геноцид был совершен в контексте массовой депортации чеченцев, ингушей, немцев Поволжья, крымских татар, калмыков и карачаевцев.[130]

Что касается судьбы крымских татар, Амир Вайнер из Стэнфордского университета пишет, что эту политику можно классифицировать как этническую чистку. В книге "Век геноцида" Лайман Х. Легтерс пишет: "Мы не можем правильно говорить о завершенном геноциде, только о процессе, который был геноцидным в своей потенциальной возможности".[131] В противовес этому мнению Джон К. Чанг утверждает, что депортации на самом деле были основаны на геноциде по этническому признаку и что "социальные историки" на Западе не смогли отстоять права маргинализированных этносов в Советском Союзе.[132] Эту точку зрения поддерживают несколько стран. 12 декабря 2015 года парламент Украины принял резолюцию, признающую депортацию крымских татар в 1944 году (сюргюнлик) геноцидом и установил 18 мая Днем памяти жертв геноцида крымских татар.[133] Парламент Латвии признал это событие актом геноцида 9 мая 2019 года.[134][135] Парламент Литвы сделал то же самое 6 июня 2019 года.[136] Парламент Канады 10 июня 2019 года принял предложение о признании депортации крымских татар геноцидом, совершенным советским диктатором Сталиным, и объявил 18 мая днем памяти.[137] В 2004 году Европейский парламент признал депортацию чеченцев и ингушей актом геноцида, заявив:[138] "Считает, что депортация всего чеченского народа в Среднюю Азию 23 февраля 1944 года по приказу Сталина представляет собой акт геноцида по смыслу Четвертой Гаагской конвенции 1907 года и Конвенции о предупреждении и пресечении преступления геноцида, принятой Генеральной Ассамблеей ООН 9 декабря 1948 года".[139]

Голод в СССР (1932—1933)

В Советском Союзе насильственные изменения в сельскохозяйственной политике (коллективизация), конфискации зерна и засухи вызвали советский голод 1932-1933 годов в Украинской ССР (Голодомор), Северо-Кавказском крае, Поволжье и Казахской ССР.[140][141][142] Голод был наиболее сильным на Украине, где его часто называют Голодомором. Значительную часть жертв голода (от 3,3 до 7,5 миллионов) составляли украинцы.[143][144][145] Другой частью голода был голод в Казахстане, также известный как Казахская катастрофа, когда погибло более 1,3 миллиона этнических казахов (около 38% населения).[146][147]

Хотя среди ученых до сих пор ведутся споры о том, был ли Голодомор геноцидом, некоторые исследователи утверждают, что сталинская политика, вызвавшая голод, могла быть разработана как атака на рост украинского национализма[148] и может подпадать под юридическое определение геноцида в Конвенции ООН о геноциде.[140][149][150][151] Голод был официально признан геноцидом Украиной и другими правительствами.[152][bv] В проекте резолюции Парламентская Ассамблея Совета Европы заявила, что голод был вызван "жестокими и преднамеренными действиями и политикой советского режима" и несет ответственность за гибель "миллионов невинных людей" в Украине, Беларуси, Казахстане, Молдове и России. Считается, что по отношению к численности населения Казахстан пострадал больше всех.[153] Относительно казахского голода Майкл Эллман утверждает, что он "кажется примером "геноцида по неосторожности", который не подпадает под действие Конвенции ООН о геноциде".[154]

Большой террор

Попытки Сталина укрепить свое положение лидера Советского Союза привели к эскалации арестов и казней, достигших кульминации в 1937-1938 годах, период, который иногда называют "ежовщиной" по имени сотрудника ЧК Николая Ежова, или эпохой Ежова, и продолжавшихся до смерти Сталина в 1953 году. Около 700 000 из них были казнены выстрелом в затылок.[156] Другие погибли от избиений и пыток во время "следственных изоляторов"[157] и в ГУЛАГе от голода, болезней, облучения и переутомления.[bw]

Аресты обычно производились со ссылкой на статью 58 (Уголовный кодекс РСФСР) о контрреволюционных законах, которая включала недонесение об изменнических действиях и, согласно поправке, добавленной в 1937 году, невыполнение назначенных обязанностей. По делам, расследованным Управлением государственной безопасности НКВД с октября 1936 года по ноябрь 1938 года, было арестовано не менее 1 710 000 человек и 724 000 человек казнено.[158] Современные исторические исследования оценивают общее число погибших от репрессий в 1937-1938 годах в 950 000-1 200 000 человек. Эти цифры учитывают неполноту официальных архивных данных и включают как смерти от расстрелов, так и смерти в ГУЛАГе в этот период.[bw] Бывшие кулаки и члены их семей составили большинство жертв: 669 929 человек были арестованы и 376 202 казнены.[159]

НКВД провел ряд национальных операций, направленных против некоторых этнических групп.[160] В общей сложности 350 000 были арестованы и 247 157 были казнены.[161] Из них польская операция НКВД, направленная против членов "Польской организации Войсковой линии", была, по-видимому, самой крупной: 140 000 арестов и 111 000 казней.[160] Хотя эти операции вполне могут представлять собой геноцид, как его определяет конвенция ООН,[160] или "мини-геноцид", по словам Саймона Себага Монтефиоре,[161] пока нет авторитетного решения о правовой характеристике этих событий.[126] Александр Николаевич Яковлев, ссылаясь на церковные документы, подсчитал, что за это время было казнено более 100 000 священников, монахов и монахинь.[162][163] Что касается преследования духовенства, Майкл Эллман заявил, что "террор 1937-38 годов против духовенства Русской православной церкви и других религий (Binner & Junge 2004) также может быть квалифицирован как геноцид".[164] Летом и осенью 1937 года Сталин направил агентов НКВД в Монгольскую Народную Республику и организовал монгольский Большой террор[165] в ходе которого было казнено около 22 000[166] или 35 000 человек[167]. Около 18 000 жертв были буддийскими ламами.[166] В Беларуси массовые захоронения нескольких тысяч гражданских лиц, убитых НКВД в 1937-1941 годах, были обнаружены в 1988 году в Курапатах.[168]

Советские убийства во время Второй мировой войны

После советского вторжения в Польшу в сентябре 1939 года оперативные группы НКВД начали удалять "враждебные советской власти элементы" с завоеванных территорий.[169] НКВД систематически применял пытки, которые часто заканчивались смертью.[170][171] По данным Польского института национальной памяти, 150 000 польских граждан погибли в результате советских репрессий во время войны.[172][173] Самые известные убийства произошли весной 1940 года, когда НКВД казнил около 21 857 польских военнопленных и интеллектуальных лидеров в результате того, что стало известно как Катынская резня.[174][175][176] Казни проводились и после аннексии стран Балтии.[177] На начальных этапах операции "Барбаросса" НКВД и приданные ему части Красной армии десятками тысяч уничтожали пленных и политических противников, прежде чем бежать от наступающих войск держав Оси.[178] На местах казней НКВД в Катыни и Медном в России, а также на "третьем поле убийств" в Пятихатках (Украина) были построены мемориальные комплексы.[179]

-

Жертвы советского НКВД во Львове, июнь 1941 года

-

Эксгумация в Катыни в 1943 году (фото делегации Международного Красного Креста)

-

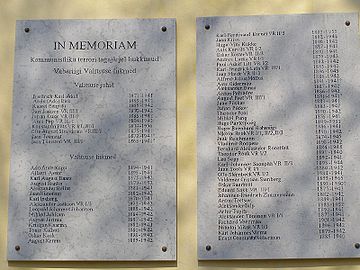

Мемориальная доска на Тоомпеа, здании правительства Эстонии, в память о членах правительства, погибших в результате коммунистического террора

Китайская Народная Республика

Китайская коммунистическая партия пришла к власти в Китае в 1949 году после долгой и кровопролитной гражданской войны между коммунистами и националистическим Гоминьданом. Историки сходятся во мнении, что после захвата власти Мао Цзэдуном его политика и политические чистки прямо или косвенно привели к гибели десятков миллионов людей.[180][181][182] Основываясь на опыте Советов, Мао считал насилие необходимым для достижения идеального общества, вытекающего из марксизма, и поэтому он планировал и осуществлял насилие в больших масштабах.[183][184]

Кампания по подавлению контрреволюционеров

Первые крупномасштабные убийства при Мао произошли во время его земельной реформы и кампании по подавлению контрреволюционеров. По словам Дэниела Голдхагена, официальные материалы исследования, опубликованные в 1948 году, показывают, что Мао предполагал, что "десятая часть крестьян", или около 50 000 000, "должна быть уничтожена", чтобы облегчить проведение аграрной реформы.[185] Точное число людей, погибших во время земельной реформы Мао, считается меньшим; по данным Рудольфа Руммеля и Филипа Шорта, было убито не менее миллиона человек.[183][186] Подавление контрреволюционеров было направлено в основном на бывших гоминдановских чиновников и интеллигенцию, которых подозревали в нелояльности.[187] Согласно Ян Куйсону, по меньшей мере 712 000 человек были казнены, а 1 290 000 были заключены в трудовые лагеря, известные как Лаогай.[188]

Большой скачок и Великий китайский голод

Бенджамин Валентино утверждает, что Великий скачок вперед стал причиной Великого китайского голода, а худшие последствия голода были направлены на врагов режима.[189] Те, кого в предыдущих кампаниях называли "черными элементами" (религиозные лидеры, правые и богатые крестьяне), погибли в наибольшем количестве, потому что им отдавался самый низкий приоритет при распределении продовольствия.[189] В книге "Великий голод Мао" историк Франк Дикёттер пишет, что "принуждение, террор и систематическое насилие были самой основой Великого скачка вперед", и это "послужило мотивацией для одного из самых смертоносных массовых убийств в истории человечества".[190] По оценкам Дикёттера, за этот период по меньшей мере 2,5 миллиона человек были суммарно убиты или замучены до смерти.[191] Его исследования в местных и провинциальных китайских архивах показывают, что число погибших составило не менее 45 миллионов человек: "В большинстве случаев партия прекрасно знала, что она морит голодом свой собственный народ".[192] На секретном совещании в Шанхае в 1959 году Мао отдал приказ о закупке трети всего зерна в сельской местности, сказав: "Когда не хватает еды, люди умирают от голода. Лучше дать половине людей умереть, чтобы другая половина могла наесться досыта".[192] В свете дополнительных доказательств вины Мао, Руммель добавил убитых во время Великого голода к общему числу жертв демоцида Мао, в результате чего общее число убитых составило 77 миллионов человек.[45][bx]

Тибет

Согласно Жан-Луи Марголину в "Черной книге коммунизма", китайские коммунисты осуществили культурный геноцид тибетцев. Марголин утверждает, что убийства в Тибете были пропорционально больше, чем в самом Китае, и "можно с полным основанием говорить о геноцидной резне из-за количества людей, которые были вовлечены в нее".[193] По словам Далай-ламы и Центральной тибетской администрации, "тибетцев не только расстреливали, но и забивали до смерти, распинали, сжигали заживо, топили, калечили, морили голодом, душили, вешали, варили заживо, закапывали заживо, четвертовали и обезглавливали".[193] Адам Джонс, ученый, специализирующийся на геноциде, утверждает, что после восстания в Тибете в 1959 году китайцы санкционировали сеансы борьбы с реакционерами, во время которых "коммунистические кадры осуждали, пытали и часто казнили врагов народа". В результате этих сеансов погибло 92 000 человек из общей численности населения около 6 миллионов. Эти смерти, подчеркнул Джонс, можно рассматривать не только как геноцид, но и как элитицид, то есть "нападение на более образованных и ориентированных на лидерство элементов среди тибетского населения".[194] Патрик Френч, бывший директор Free Tibet Campaign в Лондоне, пишет, что Free Tibet Campaign и другие группы утверждают, что в общей сложности 1,2 миллиона тибетцев были убиты китайцами с 1950 года, но после изучения архивов в Дхарамсале он не нашел "никаких доказательств, подтверждающих эту цифру".[195] Френч утверждает, что достоверное альтернативное число вряд ли будет известно, но оценивает, что до полумиллиона тибетцев погибли "как "прямой результат" политики Китайской Народной Республики", используя оценку историка Уоррена Смита в 200 000 человек, отсутствующих в статистике населения Тибетского автономного района, и распространяя этот показатель на приграничные районы.[196]

Культурная революция

По оценкам китаеведов Родерика Макфаркухара и Майкла Шенхальса, только в сельских районах Китая в результате насилия Культурной революции было убито от 750 000 до 1,5 миллиона человек.[197] Красная гвардия Мао получила карт-бланш на издевательства и убийства людей, которых считали врагами революции.[198] В августе 1966 года более 100 учителей были убиты своими учениками в западной части Пекина.[199] Финкель и Штраус пишут, что по оценкам Су до трех миллионов человек были "убиты своими соседями в ходе коллективных убийств и митингов борьбы. Это произошло, несмотря на то, что центральное правительство не издавало никаких приказов о массовых убийствах".[200]

Ян Су утверждает, что массовые убийства во время Культурной революции были вызваны "парадоксом государственного спонсорства и государственного провала"; по словам Яна, массовые убийства были сосредоточены в сельских районах в течение нескольких месяцев после создания уездных революционных комитетов, причем вероятность массовых убийств в каждой общине была тем выше, чем больше в ней было местных членов партии. Репрессии местных организаций могли быть ответом на риторику насилия, продвигаемую столицами провинций в результате массовой фракционности в этих столицах, а "пик массовых убийств совпал с двумя объявлениями из партийного центра в июле 1968 года о запрете фракционных вооруженных боев и роспуске массовых организаций";[by] Янг пишет, что правительство Мао определяло классовых врагов, используя искусственный и произвольный стандарт, чтобы решить две политические задачи - "мобилизовать массовое подчинение и разрешить конфликт элит", а эластичная природа этой категории позволяла ей "принимать геноцидальное измерение при чрезвычайных обстоятельствах".[bz]

Площадь Тяньаньмэнь

Жан-Луи Марголин утверждает, что при Дэн Сяопине было убито не менее 1000 человек в Пекине и сотни людей были казнены в сельской местности после того, как его правительство подавило демонстрации на площади Тяньаньмэнь в 1989 году.[201] Как сообщила Луиза Лим в 2014 году, группа родственников жертв в Китае под названием "Матери Тяньаньмэнь" подтвердила личности более 200 убитых.[202] Алекс Беллами пишет, что эта "трагедия знаменует собой последний случай, когда эпизод массового убийства в Восточной Азии был прекращен самими преступниками, посчитавшими, что они преуспели".[203]

-

Реплика статуи "Богиня демократии" в гонконгском музее 4 июня

-

Мемориал в память о событиях на площади Тяньаньмэнь 1989 года на Доминиканской площади во Вроцлаве, Польша

-

Статуя, расположенная в Авиле, Испания, напоминающая о событиях на площади Тяньаньмэнь

Камбоджа

Поля смерти — это ряд мест в Камбодже, где большое количество людей было убито, а их тела захоронены режимом "красных кхмеров" во время его правления в стране, которое длилось с 1975 по 1979 год, после окончания гражданской войны в Камбодже. Социолог Мартин Шоу назвал геноцид в Камбодже "чистейшим геноцидом эпохи холодной войны".[204] Результаты демографического исследования геноцида в Камбодже показали, что число погибших в стране с 1975 по 1979 год составило от 1 671 000 до 1 871 000 человек, или 21-24% от общей численности населения Камбоджи, как считалось до прихода к власти красных кхмеров.[205] По словам Бена Кирнана, количество смертей, которые были вызваны именно казнями, до сих пор неизвестно, потому что многие жертвы умерли от голода, болезней и переутомления.[205] Исследователь Крейг Этчисон из Центра документации Камбоджи предполагает, что число погибших составило от 2 до 2,5 миллионов человек, при этом "наиболее вероятная" цифра - 2,2 миллиона. Потратив пять лет на исследование около 20 000 мест захоронений, он предположил, что "в этих массовых могилах находятся останки 1 112 829 жертв казни".[206] Исследование французского демографа Марека Сливинского подсчитало чуть менее 2 миллионов неестественных смертей при красных кхмерах из 7,8 миллионов камбоджийского населения 1975 года, при этом 33,5% камбоджийских мужчин умерли при красных кхмерах по сравнению с 15,7% камбоджийских женщин.[207] Число предполагаемых жертв казни, найденных в 23 745 массовых захоронениях, оценивается в 1,3 миллиона человек, согласно академическому источнику 2009 года. Считается, что казни составляют около 60% от общего числа погибших во время геноцида, остальные жертвы погибли от голода или болезней.[208]

Хелен Файн, исследователь геноцида, утверждает, что ксенофобская идеология режима "красных кхмеров" больше похожа на "почти забытое явление национал-социализма", или фашизма, чем на коммунизм.[209] Отвечая на "аргумент Бена Кирнана о том, что режим Демократической Кампучии Пол Пота был скорее расистским и в целом тоталитарным, чем марксистским или конкретно коммунистическим", Стив Хедер утверждает, что пример такого расистского мышления в применении к меньшинству народа Чам перекликается с "определением Маркса о не имеющем истории народе, обреченном на вымирание во имя прогресса", и поэтому является частью общих концепций класса и классовой борьбы.[210] Крейг Этчисон пишет, что данные о распределении и происхождении массовых захоронений, а также внутренние документы службы безопасности красных кхмеров позволяют сделать вывод, что "большая часть насилия осуществлялась в соответствии с приказами высшего политического руководства Коммунистической партии Кампучии", а не была результатом "спонтанных эксцессов мстительной, недисциплинированной крестьянской армии",[ca] В то время как французский историк Анри Локар пишет, что ярлык фашиста был применен к Красным кхмерам Коммунистической партией Вьетнама как форма ревизионизма, но репрессии, существовавшие при правлении Красных кхмеров, были "похожи (если не сказать более смертоносны) на репрессии во всех коммунистических режимах".[207] Дэниел Голдхаген утверждает, что красные кхмеры были ксенофобами, потому что верили, что кхмеры — "единственный подлинный народ, способный построить настоящий коммунизм".[211] Стивен Роузфилд пишет, что Демократическая Кампучия была самым смертоносным из всех коммунистических режимов в расчете на душу населения, прежде всего потому, что у нее "не было жизнеспособного производственного ядра" и она "не смогла установить границы для массовых убийств".[212]

-

Мемориал в музее геноцида Туол Сленг в Пномпене

-

Массовые захоронения на Поле смерти в камбоджийском центре геноцида Чынг Эк

-

Дерево Чанкири (Дерево смерти) в Чоенг Эк, где во время геноцида были смертельно разбиты младенцы

Другие государства

Барбара Харфф и Тед Гурр пишут: "Большинство марксистско-ленинских режимов, пришедших к власти в результате длительной вооруженной борьбы в послевоенный период, совершили одно или несколько политических убийств, хотя их масштабы сильно различались".[cb] По мнению Бенджамина Валентино, большинство режимов, называвших себя коммунистическими, не совершали массовых убийств, но массовые убийства меньшего масштаба, чем его стандарт в 50 000 человек, убитых в течение пяти лет, могли иметь место в таких коммунистических государствах, как Болгария, Румыния и Восточная Германия, хотя отсутствие документов не позволяет вынести окончательное суждение о масштабах этих событий и мотивах их исполнителей.[213] Ацуси Таго и Фрэнк Уэйман пишут, что поскольку демоцид шире, чем массовые убийства или геноцид, можно сказать, что им занимались большинство коммунистических режимов, включая Советский Союз, Китай, Камбоджу, Северный Вьетнам, Восточную Германию, Польшу, Чехословакию, Венгрию, Северную Корею, Кубу, Лаос, Албанию и Югославию.[214]

Народная Республика Болгария

По словам Валентино, имеющиеся данные свидетельствуют о том, что от 50 000 до 100 000 человек могли быть убиты в Болгарии начиная с 1944 года в рамках кампании коллективизации сельского хозяйства и политических репрессий, хотя для вынесения окончательного суждения недостаточно документов.[215] В своей книге "История коммунизма в Болгарии" Динью Шарланов насчитывает около 31 000 человек, убитых режимом в период с 1944 по 1989 год.[216][217]

Восточная Германия

По мнению Валентино, от 80 000 до 100 000 человек могли быть убиты в Восточной Германии начиная с 1945 года в рамках советской кампании денацификации; другие ученые считают, что эти оценки завышены.[215][218][219]

Сразу после Второй мировой войны в оккупированной союзниками Германии и аннексированных нацистами регионах началась денацификация. В советской оккупационной зоне Германии НКВД создавал лагеря для заключенных, обычно в заброшенных нацистских концентрационных лагерях, и использовал их для интернирования предполагаемых нацистов и нацистских немецких чиновников, а также некоторых помещиков и прусских юнкеров. Согласно файлам и данным, опубликованным Министерством внутренних дел СССР в 1990 году, в лагерях содержалось 123 000 немцев и 35 000 граждан других государств. Из этих заключенных в общей сложности 786 человек были расстреляны, а 43 035 человек умерли от различных причин. Большинство смертей не были прямыми убийствами, а были вызваны вспышками дизентерии и туберкулеза. Смерть от голода также имела большие масштабы, особенно в конце 1946 - начале 1947 года, но эти смерти, по-видимому, не были преднамеренными убийствами, поскольку нехватка продовольствия была широко распространена в советской оккупационной зоне. Заключенные в "лагерях молчания", как называли специальные лагеря НКВД, не имели доступа к черному рынку, и в результате они могли получать только ту еду, которую им передавали власти. Некоторые заключенные были казнены, а другие, возможно, были замучены до смерти. В этом контексте трудно определить, можно ли отнести гибель заключенных в лагерях тишины к массовым убийствам. Также трудно определить, сколько среди погибших было немцев, восточных немцев или представителей других национальностей.[220][221]

Восточная Германия возвела Берлинскую стену после Берлинского кризиса 1961 года. Несмотря на то, что пересечение границы между Восточной и Западной Германией было возможно для мотивированных и одобренных путешественников, тысячи восточных немцев пытались дезертировать, незаконно пересекая стену. За годы существования стены (1961-1989) охранники Берлинской стены убили от 136 до 227 человек.[222][223]

Социалистическая Республика Румыния

По мнению Валентино, от 60 000 до 300 000 человек могли быть убиты в Румынии начиная с 1945 года в рамках коллективизации сельского хозяйства и политических репрессий.[215]

Социалистическая Федеративная Республика Югославия

После Второй мировой войны коммунистический режим Иосипа Броз Тито жестоко подавлял противников и совершил несколько массовых убийств военнопленных. Европейские общественные слушания о преступлениях, совершенных тоталитарными режимами, сообщают: "Решение об "уничтожении" противников должно было быть принято в ближайших кругах югославского государственного руководства, и приказ, безусловно, был отдан Верховным главнокомандующим югославской армии Иосипом Броз Тито, хотя неизвестно, когда и в какой форме".[224][225][226][227][cc]

Доминик Макголдрик пишет, что, будучи главой "высокоцентрализованной и деспотичной" диктатуры, Тито обладал огромной властью в Югославии, а его диктаторское правление осуществлялось через сложную бюрократию, которая регулярно подавляла права человека.[227] Элиотт Бехар утверждает, что "Югославия Тито была жестко контролируемым полицейским государством",[228] а за пределами Советского Союза в Югославии было больше политических заключенных, чем во всей остальной Восточной Европе вместе взятой, согласно Дэвиду Мейтсу.[229] Тайная полиция Тито была создана по образцу советского КГБ. Ее сотрудники постоянно находились под постоянным контролем и часто действовали во внесудебном порядке,[230] их жертвами становились представители интеллигенции среднего класса, либералы и демократы.[231] Югославия подписала Международный пакт о гражданских и политических правах, однако некоторым его положениям уделяется мало внимания.[232]

Северная Корея

По словам Руммеля, принудительный труд, казни и концентрационные лагеря стали причиной смерти более миллиона человек в Корейской Народно-Демократической Республике с 1948 по 1987 год.[233] По другим оценкам, только в концентрационных лагерях Северной Кореи погибло 400 000 человек.[234] В лагерях был совершен широкий спектр зверств, включая принудительные аборты, детоубийство и пытки. Бывший судья Международного уголовного суда Томас Бюргенталь, один из авторов доклада Комиссии по расследованию прав человека в Корейской Народно-Демократической Республике и ребенок, переживший Освенцим, сказал The Washington Post, "что условия в [северо]корейских тюремных лагерях такие же ужасные, или даже хуже, чем те, которые я видел и пережил в молодости в нацистских лагерях и в моей долгой профессиональной карьере в области прав человека."[235] Пьер Ригуло оценивает 100 000 казней, 1,5 миллиона смертей через концентрационные лагеря и рабский труд, и 500 000 смертей от голода.[236]

Голод, унесший до миллиона жизней, был описан как результат экономической политики правительства Северной Кореи[237] и преднамеренного "террора-голода".[238] В 2010 году Стивен Роузфилд заявил, что "Красный холокост" "все еще продолжается в Северной Корее", поскольку Ким Чен Ир "отказывается отказаться от массовых убийств".[239] Адам Джонс приводит утверждение журналиста Джаспера Беккера о том, что голод был формой массового убийства или геноцида из-за политических манипуляций с продовольствием.[240] Оценки, основанные на переписи населения Северной Кореи 2008 года, предполагают от 240 000 до 420 000 избыточных смертей в результате северокорейского голода 1990-х годов и демографическое воздействие в виде уменьшения численности населения Северной Кореи на 600 000-850 000 человек в 2008 году в результате плохих условий жизни после голода.[241]

Демократическая Республика Вьетнам

Валентино приписывает 80 000-200 000 смертей "массовым убийствам коммунистов" в Северном и Южном Вьетнаме.[242]

Согласно исследованиям, основанным на вьетнамских и венгерских архивных данных, во время земельной реформы Северного Вьетнама с 1953 по 1956 год было казнено до 15 000 предполагаемых помещиков.[cd][243][244] Руководство Северного Вьетнама заранее планировало казнить 0,1% населения Северного Вьетнама (в 1955 году оно оценивалось в 13,5 млн. человек) как "реакционных или злых помещиков", хотя на практике это соотношение могло меняться.[245][246] В ходе кампании по земельной реформе были допущены драматические ошибки.[247] Ву Туонг утверждает, что количество казней во время земельной реформы в Северном Вьетнаме было пропорционально сопоставимо с количеством казней во время земельной реформы в Китае с 1949 по 1952 год.[245]

Куба

Согласно исследованиям Джея Улфелдера и Бенджамина Валентино, посвященным оценке рисков спонсируемых государством массовых убийств, где массовое убийство определяется как "действия государственных агентов, приводящие к преднамеренной гибели не менее 1 000 человек из отдельных групп в период продолжительного насилия", правительство Фиделя Кастро на Кубе убило от 5 000 до 8 335 человек в рамках кампании политических репрессий в период с 1959 по 1970 год.[248]

Демократическая Республика Афганистан

По мнению Фрэнка Уэймана и Ацуси Таго, хотя Демократическая Республика Афганистан часто рассматривается как пример коммунистического геноцида, она представляет собой пограничный случай.[214] До советско-афганской войны Народно-демократическая партия Афганистана казнила от 10 000 до 27 000 человек, в основном в тюрьме Пули-Чархи.[249][250][251] Были эксгумированы массовые захоронения расстрелянных заключенных, относящиеся к советской эпохе.[252]

После вторжения в 1979 году советские войска установили марионеточное правительство Бабрака Кармаля. К 1987 году около 80% территории страны постоянно контролировалось ни прокоммунистическим правительством и поддерживающими его советскими войсками, ни вооруженной оппозицией. Чтобы изменить баланс, Советский Союз использовал тактику, которая представляла собой сочетание политики выжженной земли и геноцида мигрантов. Систематически сжигая посевы и разрушая деревни в мятежных провинциях, а также подвергая ответным бомбардировкам целые деревни, подозреваемые в укрывательстве или поддержке сопротивления, Советский Союз пытался заставить местное население переселиться на контролируемую Советским Союзом территорию, тем самым лишая вооруженную оппозицию поддержки.[253] Валентино приписывает от 950 000 до 1 280 000 смертей гражданского населения советскому вторжению и оккупации страны в период с 1978 по 1989 год, в основном в качестве контрпартизанских массовых убийств.[254] К началу 1990-х годов примерно одна треть населения Афганистана покинула страну.[ce] M. Хассан Какар сказал, что "афганцы - одна из последних жертв геноцида со стороны сверхдержавы".[255]

Народно-Демократическая Республика Эфиопия

По оценкам Amnesty International, во время эфиопского "красного террора" 1977 и 1978 годов было убито полмиллиона человек.[256][257][258] Во время террора группы людей загонялись в церкви, которые затем сжигались, а женщины подвергались систематическим изнасилованиям со стороны солдат.[259] Фонд спасения детей сообщил, что жертвами "красного террора" стали не только взрослые, но и 1000 и более детей, в основном в возрасте от одиннадцати до тринадцати лет, трупы которых были оставлены на улицах Аддис-Абебы.[256] Утверждается, что эфиопский диктатор Менгисту Хайле Мариам убивал политических противников голыми руками.[260]

Споры о голоде

По мнению историка Дж. Арча Гетти, более половины из 100 миллионов смертей, которые приписывают коммунизму, были вызваны голодом.[261] Стефан Куртуа утверждает, что многие коммунистические режимы вызывали голод в своих попытках насильственной коллективизации сельского хозяйства и систематически использовали его в качестве оружия, контролируя поставки продовольствия и распределяя его по политическим мотивам. Куртуа утверждает, что "в период после 1918 года только коммунистические страны пережили такой голод, который привел к гибели сотен тысяч, а в некоторых случаях и миллионов людей". И снова в 1980-х годах две африканские страны, провозгласившие себя марксистско-ленинскими, Эфиопия и Мозамбик, были единственными странами, пережившими эти смертоносные голоды".[cf]

Ученые Стивен Г. Уиткрофт, Р. В. Дэвис и Марк Таугер отвергают идею о том, что украинский голод был актом геноцида, намеренно осуществленным советским правительством.[262][263] Гетти утверждает, что "подавляющее большинство ученых, работающих с новыми архивами, считают, что ужасный голод 1930-х годов был результатом сталинской неуклюжести и жесткости, а не какого-то геноцидного плана".[261] Писатель Александр Солженицын в статье в "Известиях" от 2 апреля 2008 года высказал мнение, что голод 1930-х годов на Украине ничем не отличался от российского голода 1921-1922 годов, поскольку оба были вызваны безжалостным ограблением крестьян большевистскими зернозаготовками.[264]