沙斐儀派

| 系列條目 |

| 遜尼派 |

|---|

|

|

歷史(迫害) |

沙斐儀派(阿拉伯語:شافعي,拉丁化Šāfiʿī ;英語:Shafi'i)[1]、沙菲耶派[2],是遜尼派伊斯蘭四大教法學中的一大派別,由阿拉伯學者穆罕默德·本·伊德里斯·沙斐儀於公元9世紀初創立。[3]另外三大學派是哈乃斐派、罕百里派和馬立克派。

在早期的伊斯蘭教中,沙斐儀派是伊斯蘭教法學中遵循者最多的一派。然而隨着奧斯曼帝國的擴張,在部分穆斯林聚居區,其主導地位被哈乃斐派取代。[4]

主要原則

[編輯]沙斐儀學派規定了五個權威的教法來源。按照等級劃分的順序,首先依靠的是古蘭經,其次是聖訓;[5][4]當古蘭經和聖訓解釋模稜兩可時,沙斐儀學派則從「公議」(先知穆罕默德同伴們的一致意見)中尋求教法指導;[6] 如果沒有一致意見,則依據「伊智提哈德」(穆罕默德同伴的個人意見);最後再依靠類比。[5]

沙斐儀學派否認「伊斯提哈桑」(又譯「優選」,在有更強的證據時放棄以前判例作出的新裁決)和「伊斯提斯拉赫」(又譯「公益」,在公共利益基礎上進行的判決)這兩個原則的權威性,儘管他們被其他教法學派承認。[7][8]「優選」和「公益」這兩個原則沒有古蘭經或聖訓的原文作為基礎,只是伊斯蘭教法學家們為了推廣伊斯蘭教的所作的理解。[9]沙斐儀學派認為這兩個原則是依靠的是人類的意見,可能產生腐敗現象或會隨着政治環境發生改變,因此拒絕承認其作為法學來源。[7][8]

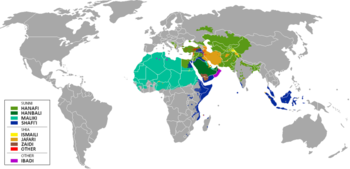

分布

[編輯]- 非洲:吉布提,索馬里,埃塞俄比亞,埃及東部,以及東非印度洋沿岸地區。[11]

- 中東: 也門,庫爾德斯坦,以色列,黎巴嫩,約旦部分地區,巴勒斯坦,以及沙特阿拉伯部分地區。

- 高加索:阿塞拜疆部分地區[12]。

- 南亞和東南亞:印度尼西亞,馬來西亞,馬爾代夫,斯里蘭卡,印度西海岸,新加坡,緬甸,泰國,文萊,以及菲律賓南部地區。其中,伊斯蘭教遜尼派沙斐儀學派是文萊和馬來西亞的官方宗教。[13][14][15]

主要觀點

[編輯]不同穆斯林社區實行伊斯蘭教法的嚴格程度有所差異,部分社區只實行教法的部分方面,如婚姻、繼承等。[16][17][18]下述為沙斐儀派伊斯蘭教法的觀點。

叛教

[編輯]伊斯蘭教法學的各個學派都認為叛教是一種罪行。沙斐儀學派對於叛教者首先給予三天的時間等待其悔改[19][20][21],若拒不悔改,傳統的懲罰措施是處以死刑,無論是男性或女性。[22][21]另外叛教者還要負民事責任,其財產要被沒收並分發給穆斯林親屬,其婚姻宣布無效,子女交由國家監護。[22]

褻瀆

[編輯]沙斐儀派認為褻瀆是指侮辱或貶低安拉、穆罕默德或與伊斯蘭教相關其他事物的行為[23],而褻瀆和叛教是兩種罪名。對於褻瀆者,沙斐儀學派也給予悔改的機會,拒不悔改者傳統上處以死刑,無論男性或女性。[24][25]

石刑

[編輯]對於通姦或同性戀等伊斯蘭教所禁止的性行為,沙斐儀學派認為應當處以石刑。如果被指控者未婚,則可改為公開鞭刑。[26]沙斐儀學派認可自我陳述、四個男性目擊證人的證詞(不接受女性的證詞)以及懷孕(有時會有爭議)為非法性行為的證據。[27]

彩禮

[編輯]與其他學派不同,沙斐儀學派沒有規定結婚時穆斯林男方家庭必須付給女方的彩禮金額的最低值。[28]

其他觀點

[編輯]- 與其他遜尼派伊斯蘭教法學學派一樣,沙斐儀派也規定最小的結婚年齡為:男性12歲,女性9歲。而成年的年齡是:男性18歲,女性17歲,成年之後可獨自訂立婚約。監護人有權安排未成年人的婚姻。[29]

- 傳統的沙斐儀學派認為,男方有權和女方離婚,但女方不能首先向男方提出離婚。[30]

- 其他教法學派禁止下國際象棋,而沙斐儀學派只是不提倡。[31]

- 沙斐儀派禁止音樂、歌唱與舞蹈,這與其他學派的觀點相似[32][33],並且認為所有的樂器都應當被摧毀。[34]

- 沙斐儀派學者禁止對任何有生命的物體進行描繪、繪畫。[35][36][37]

- 歷史上曾有沙斐儀學派的文獻批准過女性割禮,而沙斐儀學派的創始人認為男性和女性都有接受割禮的義務。[38][39]

- 沙斐儀學派禁止剃鬚,而其他學派只是不提倡。[40]

沙斐儀學派著名人物

[編輯]參見

[編輯]參考資料

[編輯]- ^ 思想的继承与创新. 中國社會科學網. 2014-11-28 [2015-04-29]. (原始內容存檔於2016-03-04) (中文).

- ^ 康·茨威格特; 海·克茨. 伊斯兰法概说. 環球法律評論. 1984年3月, (3): 8 [2020-04-11]. (原始內容存檔於2020-09-02).

- ^ Abdullah Saeed (2008), The Qur'an: An Introduction, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415421256, p. 17

- ^ 4.0 4.1 Shafi'iyyah (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) Bulend Shanay, Lancaster University

- ^ 5.0 5.1 Hisham M. Ramadan (2006), Understanding Islamic Law: From Classical to Contemporary, Rowman Altamira, ISBN 978-0759109919, pp. 27-28

- ^ Syafiq Hasyim (2005), Understanding Women in Islam: An Indonesian Perspective, Equinox, ISBN 978-9793780191, pp. 75-77

- ^ 7.0 7.1 Istislah (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) The Oxford Dictionary of Islam, Oxford University Press

- ^ 8.0 8.1 Istihsan (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) The Oxford Dictionary of Islam, Oxford University Press

- ^ Lloyd Ridgeon (2003), Major World Religions: From Their Origins To The Present, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415297967, pp. 259-262

- ^ Jurisprudence and Law - Islam (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) Reorienting the Veil, University of North Carolina (2009)

- ^ UNION OF THE COMOROS 2013 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) U.S. State Department (2014), Quote: "The law provides sanctions for any religious practice other than the Sunni Shafi』i doctrine of Islam and for prosecution of converts from Islam, and bans proselytizing for any religion except Islam."

- ^ Islam in Azerbaijan (Historical Background) (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館), Altay Goyushov, CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 44, 20 November 2012

- ^ Brunei. CIA World Factbook. 2011 [13 January 2011]. (原始內容存檔於2015-07-21).

- ^ 存档副本. [2015-05-01]. (原始內容存檔於2018-12-28).

- ^ Wu & Hickling, p. 35.

- ^ Islam: Governing under Sharia (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) Toni Johnson and Mohammed Aly Sergie, Council on Foreign Relations (2013)

- ^ Amanat & Griffel (2007), SHARI’A: ISLAMIC LAW IN THE CONTEMPORARY CONTEXT, Stanford University Press, ISBN 978-0804756396

- ^ I have a right to. BBC World Service. [24 February 2013]. (原始內容存檔於2018-12-24).

- ^ Mohamed El-Awa (1993), Punishment in Islamic Law, American Trust Publications, ISBN 978-0892591428, pp 1-68

- ^ Frank Griffel (2001), Toleration and exclusion: al-Shafi 『i and al-Ghazali on the treatment of apostates, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 64(03): 339-354

- ^ 21.0 21.1 David Forte, Islam’s Trajectory (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館), Revue des Sciences Politiques, No. 29 (2011), pages 92-101

- ^ 22.0 22.1 Peters & De Vries (1976), Apostasy in Islam (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館), Die Welt des Islams, Vol. 17, Issue 1/4, pp 1-25

- ^ Aḥmad ibn Luʼluʼ Ibn al-Naqīb (Trans: Noah Ha Mim Keller, 1997), The Reliance of the Traveller, ISBN 978-0915957729

- ^ L Wiederhold L, Blasphemy against the Prophet Muhammad and his companions (sabb al-rasul, sabb al-sahabah) : The introduction of the topic into Shafi'i legal literature, Jrnl of Sem Studies, Oxford University Press, 42(1), pp. 39-70

- ^ P Smith (2003), Speak No Evil: Apostasy, Blasphemy and Heresy in Malaysian Syariah Law, UC Davis Journal Int'l Law & Policy, 10, pp. 357-373;

- F Griffel (2001), Toleration and exclusion: al-Shafi 『i and al-Ghazali on the treatment of apostates, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 64(3), pp. 339-354

- ^ Elyse Semerdjian (2008), "Off the Straight Path": Illicit Sex, Law, and Community in Ottoman Aleppo, Syracuse University Press, ISBN 978-0815631736, pp. 22-23

- ^ Elyse Semerdjian (2008), "Off the Straight Path": Illicit Sex, Law, and Community in Ottoman Aleppo, Syracuse University Press, ISBN 978-0815631736, p. 25

- ^ K Ali (2010), Marriage and Slavery in Early Islam, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0674050594, pp. 56-57

- ^ Lynn Welchman (2000), Beyond the Code: Muslim Family Law and the Shariʼa Judiciary, Brill, ISBN 978-9041188595, pp. 108-110

- ^ K Ali (2010), Marriage and Slavery in Early Islam, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0674050594, pp. 178-179

- ^ The Word of Islam - Page 102, John Alden Williams - 1994

- ^ L. Ali Khan and Hisham M. Ramadan (2011), Contemporary Ijtihad: Limits and Controversies, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0748641284, pp. 72-75

- ^ M Cook (2010), Commanding Right and Forbidding Wrong in Islamic Thought, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521130936, pp. 91-103, 145-182

- ^ MA Cook (2003), Forbidding Wrong in Islam: An Introduction, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521536028, pp. 31-42, 60-68, 104-129

- ^ Thomas W. Arnold (2004), Painting in Islam: A Study of the Place of Pictorial Art in Muslim Culture, Gorgias Press, ISBN 978-1593331214, p. 9

- ^ Zaky Hassan (1944), The attitude of Islam towards painting, Bulletin of the Faculty ofArts (Cairo University), Vol. 7, pp. 1-15

- ^ Isa Salman (1969), Islam and figurative arts, Sumer, Vol. 25, pp. 59-96

- ^ Anne Meneley (1996), Tournaments of Value: Sociability and Hierarchy in a Yemeni Town, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 978-0802078681, p. 84, footnote 8

- ^

- The Different Aspects of Islamic Culture p 436, Abdelwahab Bouhdiba, Muḥammad Maʻrūf al- Dawālībī - 1998

- Self-Determination and Women's Rights in Muslim Societies - Page 129, Chitra Raghavan, James P. Levine - 2012

- ^ Reliance of the Traveller - Page 58, Nuh Mim Keller - 1994

- ^ Margaret Smith, Al-Ghazali, The Mystic, p. 47

- ^ Lyons & Jackson 1982,第41頁

- ^ I.M.N. Al-Jubouri, History of Islamic Philosophy: With View of Greek Philosophy and Early History of Islam, p 182. ISBN 0755210115